Post Desire

The Art of Oblivion

“... just as early industrial capitalism moved the focus of existence from being to having, post-industrial culture has moved that focus from having to appearing.” ― Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle

Art has always lived at the edge between structure and entropy, whether metaphysically, psychologically, metaphorically, symbolically or directly. Neolithic cave paintings were ritualistic in their attempt to bolster humanities’ fragility against overwhelming odds. Simple hand prints on cave walls affirmed our raison d’être as we fought in our terribly short lives against the climactic and barbarous conditions omnipresent then. In a geological heartbeat we have returned to a place where similar conditions await on the near time horizon.

As the constructs of civilization began when the Natufians effectively settled some 12,000 years ago in the Levant, the seed was planted that humans would from then on, try to manufacture their environment. The rapid recognition that water could be harnessed to perpetuate an unnatural agricultural cycle led to animal domestication, villages, trade, money, etc. Art evolved slightly beyond being the bridge between terror and safety, to the bridge between the sublime (i.e. offerings to the gods) and domestication (pottery, decoration, etc.) Art served as a metaphor that repressed terror, and enabled us to overcome the elements by creating agriculture, animal husbandry and eventually production. Or so we thought. We wore icons that mimicked Gaia or Mother Earth which suppressed memories of the wild, ultimately leading us to commit matricide. It took us just 10,000 years to subjugate the global environment to the extent that we created an irreversible trend in its systems. There is no artistic symbol or metaphor adequate to unpack the dimensions of our impact on the globe. Perhaps this is why the art world has largely regressed into the tortured space of Wall Street’s Capitalism.

I have always been a believer in the sublime in art. From my early days of artistic formation I was drawn to works that lived outside or beyond the dimensions of humanity. I remember the first time I saw James Rosenquist’s F-111, mesmerized by the bravado of its scale and metaphorical power. Since those high school days I’ve seen many works of art that captivate the imagination with their grasping at the impenetrable void. Not one work in my lifetime has moved me as much as watching a section of glacier the size of Manhattan calving off of Greenland in the movie Chasing Ice.

We don’t really understand scale as human beings. Our neolithic brains have great difficulty rationalizing large scale. How do we assimilate 7.4 cubic km of ice crashing off the Ilulissat glacier in Greenland? That is enough fresh water to provide 3 liters (0.79 gallons) of fresh drinking water to every person on Earth for 348 days. The Great Pyramid of Giza is roughly 2,500,000 cubic meters or 0.0025 cubic kilometers. Therefore, the ice that calved in Chasing Ice represents the equivalent of 2,800 Giza Pyramids. The section that is shown on film breaking free represents a tiny fraction of the endangered remaining ice flows in both Greenland and the Antarctic. How does art act as a bridge now, between the terrors of climate change and humanity? Has art served for too long as an agent provocateur in our understanding of environment?

[vimeo 89928979 w=500 h=281]

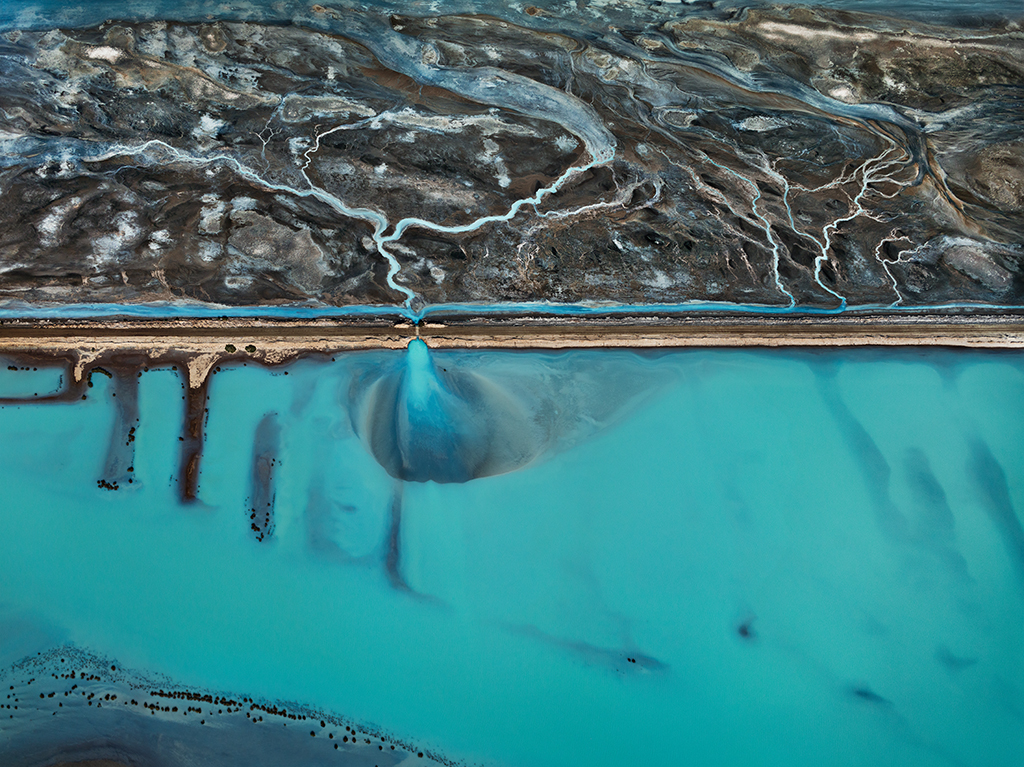

A film just released (June 2014) by Patagonia called DamNation reveals the tragedy of the U. S. post-war dam building boom of 1950 to 1970. During that period of time 30,000 dams were built across the United States in a frenzy to harness nature and build a more powerful, prosperous nation. Currently there are 80,000 dams in the U.S., only 2540 of which produce any hydropower at all. Many of these dams counterintuitively destroyed habitat that now, under the current conditions of climate change, only worsen our dilemma. The movie focuses primarily on two regions of the country where hydropower was seen as a necessary and potent way to sustain the nation’s growth, the Pacific Northwest and the Western/Southwest regions of the U.S. One of the most intriguing aspects of the film is the dialogue around what I would consider performance art pieces. These symbolic gestures, first created by Earth First when they rolled a giant piece of black plastic down the front of the Glen Canyon Dam to signify it’s need to be severed, are unintentional art performances with the potential power to speak plainly to the larger symbol, the dam itself. In 1987 Earth First painted a giant crack on the (now removed) Elwha River dam to bring awareness to the destruction of millennial-old salmon spawning grounds blocked by the dam. Watching the movie, it struck me that a possible future for art in the 21st century is not activism per se, but the creation of experiences on human scale that once again bridge the divide between terror and security.

Ed Ayres, founder of WorldWatch Institute has said, “We are being confronted by something so completely outside our collective experience that we don’t really see it, even when the evidence is overwhelming. For us, that ‘something’ is a blitz of enormous biological and physical alterations in the world that as been sustaining us.” Here is one of art’s fundamental roles, to expose the dimensions of human imagination beyond our everyday experiences. Art is uniquely qualified to contextualize the impending trauma that is already unfolding as a result of the beginnings of the Anthropocene era. What we so desperately need from art now is a parsing of the terrors of the sublime, of climate change, so that we might imagine a way to at the very least, to plug the gushing wound. What we don’t need from art is more pandering to money which is actually pandering to the past, the status quo which inevitably makes it less art and more visual onanism.

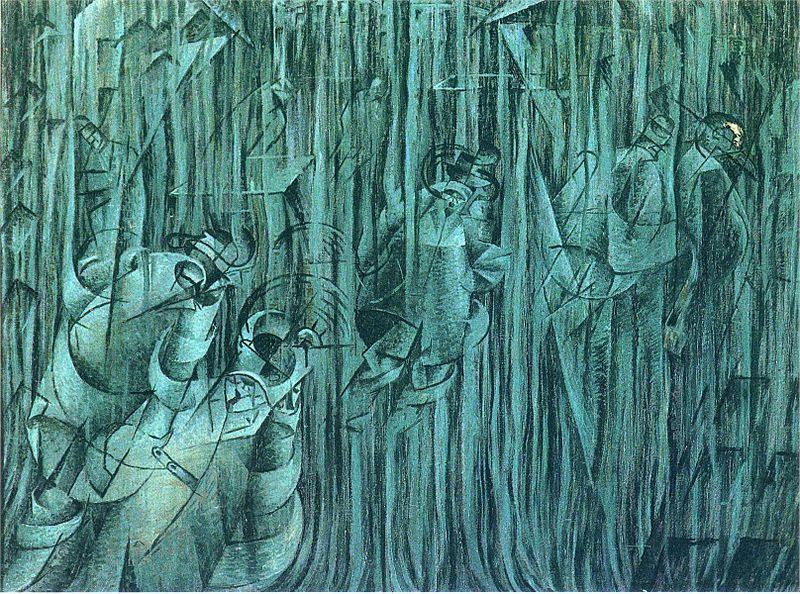

There is a long standing tradition in arts relationship to environment that focuses on the symbolic and the sublime. Anselm Keifer arguably has taken this to its logical end point with his majestic, allegorical paintings and sculptures that use landscape as a symbolic metaphor to translate the myth and memory of Germany. Keifer’s has combined those elements nascent in Bierstadt, Turner, Cezanne and even Rothko and pushed them into a dimension so heavily laden with teleology they immolate landscape painting as a useful genre altogether. “The real problem—what we might call the Kiefer syndrome—is whether it is possible to take myth seriously on its own terms, and to respect its coherence and complexity, without becoming morally blinded by its poetic power.” Beyond this arose the land art aesthetes, engaging the environment directly. Unfortunately, and as extraordinary this work can be, it is increasingly become a mirror for the hubris of mankind's intersection with the environment rather than an elegy for its enduring and sustaining presence. Didactic attempts to unravel in the aesthetic our place on this blue dot is dead. Art must find a new way forward.

There is no other problem, issue or need, there is only one and in that sense we should take heart that our jobs as artists have actually been radically simplified in terms of focus. If art is a reflection of the now, the state of humanity acting as a mirror unto itself, then the only thing that needs mirroring is our own impending doom. If we cannot see fit to displace short term arrogance of our pitiful achievements in order to maintain what’s left of the wildness of this Earth, then we will surely perish as a species. “Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, and as vital to our lives as water and good bread. A civilization which destroys what little remains of the wild, the spare, the original, is cutting itself off from its origins and betraying the principle of civilization itself.” Art has much to learn from people like the late Edward Abbey and I think it comes down to effective strategies. For years I’ve been in awe of those artists whose power resides in poetic scale and what many might describe as machismo. The work of Walter De Maria, James Turrell, Olafur Eliasson, Anselm Kiefer, and Richard Serra have captivated me due to their elegiac form, sense of grandeur and push beyond human scale. I still believe there is a place for works like Lightning Field, Roden Crater or Serra’s great tilted steel forms. I am now coming to believe these works are looking more and more aligned with an age that has passed. The time of humans will only be sustained if we stop imposing ourselves so directly on the environment and begin to deconstruct some of the impositions from our past. This is not to say that humanity and art should embrace some ecotopia, because that is both impossible and equally salacious. Rather there is a middle way—a measured middle ground—and I’m hopeful art will show us the way. There are extant artists in our presence we can look to. The work of Gabriel Orozco, Mel Chin, Hans Haacke, and Diana Lynn Thompson, to name a few, are artists who provide an alternative to the monumental.

Mel Chin & Hans Haacke artworks

My nature is to be optimistic, but the current conditions of the world are making that more challenging each day. There is no real paradigm shift, no terror in people’s eyes over the imminent loss of the Western Ice Shelf of Antarctica, the ever increasing average yearly global surface temperatures of the planet or the desertification of the San Juaquin Valley. In a land of relative comfort and prosperity enamored with corporate consumerism, it is easy to understand why this is so. Films like DamNation, Chasing Ice, and Do The Math can only take us so far. Documentaries, as powerful and emotionally wrenching as they can be, are stunted by their transient, filmic nature. They are also a form of preaching to the choir. A new kind of subtle art might open the door for the middle, the unconvinced and the comfortable classes to see the real terror around us and take action. At least that’s my optimistic hope. There are points of light in the darkness but the real question is will we have the courage to flood the room with light completely before we run out of time. Once again I’ll share Schama’s words as a nod to this hopefulness;

“…it seems to me that neither the frontiers between the wild and the cultivated, nor those that lie between the past and the present, are so easily fixed. Whether we scramble the slopes or ramble the woods, our Western sensibilities carry a bulging backpack of myth and recollection. We walk Denecourt’s trail; we climb Petrach’s meandering path. We should not support this history apologetically or resentfully. for within its bag are fruitful gifts—not only things that we have taken from the land but things that we can plant upon it. And though ti may sometimes seem that our impatient appetite for produce has round the earth to thin and shifting dust, we need only poke below the subsoil of its surface to discover an obstinately rich loam of memory. It is not that we are any more virtuous or wiser than the most pessimistic environmentalists supposes. It is just that we are more retentive. The sum of our pasts, generation laid over enervation, like the slow mold of the seasons, forms the compost of our future. We live off it.”