The Bravo TV series, Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, now in its second season, is a ‘reality’ television show acutely focused on the world of art. Why not? Reality television which began with game shows and found its seat of power in “The Real World” began to wain as a genre in the mid aughts and needed fresh blood. Dancing with the Stars, a British born ballroom dancing escapade bore the first real fruit in its adoption in America, a country far more obsessed with celebrity, or at least a country bearing more celebrity offspring. The brilliance or sadism or both of juxtaposing professional ballroom dancers with ‘B’ and sometimes ‘C’ list celebrities (and now offspring of vice presidential wanna-be’s) was an inspiration befitting a Warholian wet dream. That inspired dalliance, has become the pro forma reality TV format. It extends from America’s Next Top Model through Project Runway to American Idol to Top Chef. The central theme being, any amateur with enough gusto and narcissism can become a professional sharing the limelight with the likes of Heidi Klum, Alexandra Beller, Justin Vernon (Bon Iver) or Gordon Ramsey. And now, that conceit tilting against the windmills of Malcolm Gladwell, is fully realized in the ultimate enigma of contemporary culture — fine art. Forgive us Narcissus.

The Bravo TV series, Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, now in its second season, is a ‘reality’ television show acutely focused on the world of art. Why not? Reality television which began with game shows and found its seat of power in “The Real World” began to wain as a genre in the mid aughts and needed fresh blood. Dancing with the Stars, a British born ballroom dancing escapade bore the first real fruit in its adoption in America, a country far more obsessed with celebrity, or at least a country bearing more celebrity offspring. The brilliance or sadism or both of juxtaposing professional ballroom dancers with ‘B’ and sometimes ‘C’ list celebrities (and now offspring of vice presidential wanna-be’s) was an inspiration befitting a Warholian wet dream. That inspired dalliance, has become the pro forma reality TV format. It extends from America’s Next Top Model through Project Runway to American Idol to Top Chef. The central theme being, any amateur with enough gusto and narcissism can become a professional sharing the limelight with the likes of Heidi Klum, Alexandra Beller, Justin Vernon (Bon Iver) or Gordon Ramsey. And now, that conceit tilting against the windmills of Malcolm Gladwell, is fully realized in the ultimate enigma of contemporary culture — fine art. Forgive us Narcissus.

The most prominent member, with the most street cred in the art world on Work of Art, is the Senior Art Critic for New York Magazine, Jerry Saltz. A former art student at the famous School of the Art Institute of Chicago and later an adjunct professor there, he fell away from art making after college. In fact at one point in his history, he was a long haul trucker. Saltz has quoted Charlie Parker’s “If you don’t play the saxophone for a year, you get a year better.” and added

After two years of not working at all and fretting about it all the time I stopped making art altogether. I haven’t made it since. I miss it. I miss being able to listen to music while writing, working with materials, and the amazing psychic space making art creates. Soon, I became a long distance truck driver; my CB radio name was the Jewish Cowboy. I’d come on and say ‘Shalom, partner.’ While driving trucks I thought about how much I loved art and the art world. I knew I wanted to be part of that world no matter what. I thought writing criticism would be easy, so I decided to become a critic.

In 1998 he took a position as the Senior Art Critic for the Village Voice newspaper in New York, then the dominant force in art taste making in arts capital city. After eight years of writing for the Voice and Art in America, he took the position he still maintains today. He is an ardent fan of irony and Warholian Pop descendants and is a progressive adopter of the Facebook culture, using his profile page as both a dais and community bulletin board. In 2009 ArtReview named him the 73rd most powerful figure in the art world. Saltz was a clear choice as an anchor for Work of Art because he maintains a very populist vernacular about a culture which is the farthest from populist. He is witty and self-deprecating, which removes the stain of elitism his cohorts, including his wife Robert Smith (Senior Art Critic for the New York Times) are often coated with by mainstream media and middle America. In other words, he was the perfect combination of art world establishment and affable schlub. We don’t much care for informed criticism in this country, but we love our pundits and Saltz is the closest thing to a pundit the New York art scene has.

Being an art critic is to be a critic of the core of societies future. Most of the time it must appear as though one is criticizing the air we breath or the invisible man. If we are to believe the seriousness of Saltz, and Bill Powers having been quoted they hope the show creates a bigger audience for art as a whole, then we should take a critical look at the show. In the book The Crisis of Criticism, the editor, Maurice Berger lays out a beautiful description of what criticism can be in practice;

The strongest criticism today—the kind that offers the greatest hope for the vitality and future of the discipline—is capable of engaging, guiding, directing, and influencing culture, even stimulating new forms of practice and expression. The strongest criticism serves as a dynamic, critical force, rather than a s an act of boosterism. The strongest criticism uses language and rhetoric not merely for descriptive or evaluative purposes but as means of inspiration, provocation, emotional connection, and experimentation.

We are all participants in the absurdity of life, but to play in the art arena/world one must be just a little bit unbalanced. The making of art in a fiercely capitalist society is hard enough, but the effete inner circle of the New York art world, the so-called epicenter of great art, is nearly impossible. The gallery owners, auction houses and art fair doyens of New York live by what Robert Hughes said, “The new job of art is to sit on the wall and get more expensive." It is no surprise that when Wall Street takes a dive, so follows the art world. Do those who create wish to be judged by those who wish they could? Is it possible for someone who stopped ‘making’ to have an eye for that which they no longer have the personal will to create themselves? Aren’t we talking about taste-making here and the very Renaissance idea of verity in the form of established beauty within the guidelines of the cultural elite? Isn’t that why in recent years, without shame, Versailles has been the host to solo exhibitions by the Pop Art pugilists Jeff Koons and Haruki Murakami? I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the executive producer of the show is the former co-star of Sex in the City, a TV show based largely on gossip and absurd fashion. That the two leading members of the art world who are judges, are fans of Warhol’s legacy is no accident either. To add insult to injury (or irony?), Mr. Powers’ co-owns the Half Gallery with the infamous author James Frey. Yes, that James Frey, the one that hoodwinked Oprah and convinced a ton of people to buy into his false biography of pain-killer-free dental rehab. As icing on this illustrious Pop cake, we have the ‘model’ China Chow and her ridiculous haute couture dresses and perilous high heels (a mimic of Carrie from SITC perhaps?) and the seemingly always mystified Simon de Pury the co-founder of one of the largest art auction houses in the world. Shakespeare said it best, “Like a fair house built on another man's ground; so that I have lost my edifice by mistaking the place where I erected it.”

I am not making an argument here against criticism or Jerry Saltz’s particular criticism, but rather its waning value to 21st century popular culture. An accidental conspiracy of the internet and capitalism has promoted amateurism above professionalism. Indeed the current art world itself, may be the most devilish trader in this idea. Saltz, as a cultural critic, has abdicated his responsibility to elevate our understanding of art. Despite the fact a liberal arts education in America is vanishing, we have never been a culture, as Europe is, well versed in the idiosyncrasies of fine art. Our patience is low and our drive is toward capital and superiority at all costs. Art does not fit into that notion very well at all. Publicly supported/sponsored art just makes sense in Europe, where as in the U.S. it requires complicity in a lie. A lie that we are a culture at all and the public will “get it” if we simply set public money aside for it. Whether it’s Serra’s Tilted Arc, Mapplethorpe’s S & M photography or Ofili’s elephant shit Virgin Mother, we as a nation are uncomfortable with conceptual thinking. The only conceptual thinking tolerated is of those who make so much money it obscures criticism. I’m thinking of the late Steve Jobs here. Ask any random American on the street what gestalt means or who Andre Serrano (a guest critic on the show), Damian Hirst or Jeff Koons are and you’ll get an equally quizzical tilt of the head. All of the aforementioned artists would be referred to as ‘blue chip’ in the art world and their work sells for thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars in the leading galleries.

I am not making an argument here against criticism or Jerry Saltz’s particular criticism, but rather its waning value to 21st century popular culture. An accidental conspiracy of the internet and capitalism has promoted amateurism above professionalism. Indeed the current art world itself, may be the most devilish trader in this idea. Saltz, as a cultural critic, has abdicated his responsibility to elevate our understanding of art. Despite the fact a liberal arts education in America is vanishing, we have never been a culture, as Europe is, well versed in the idiosyncrasies of fine art. Our patience is low and our drive is toward capital and superiority at all costs. Art does not fit into that notion very well at all. Publicly supported/sponsored art just makes sense in Europe, where as in the U.S. it requires complicity in a lie. A lie that we are a culture at all and the public will “get it” if we simply set public money aside for it. Whether it’s Serra’s Tilted Arc, Mapplethorpe’s S & M photography or Ofili’s elephant shit Virgin Mother, we as a nation are uncomfortable with conceptual thinking. The only conceptual thinking tolerated is of those who make so much money it obscures criticism. I’m thinking of the late Steve Jobs here. Ask any random American on the street what gestalt means or who Andre Serrano (a guest critic on the show), Damian Hirst or Jeff Koons are and you’ll get an equally quizzical tilt of the head. All of the aforementioned artists would be referred to as ‘blue chip’ in the art world and their work sells for thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars in the leading galleries.

Ultimately, my disappointment with Saltz and company in The Making of Art comes down to something said by Howard Beale (Peter Finch) in the masterful 1976 movie, Network;

I don't have to tell you things are bad. Everybody knows things are bad. It's a depression. Everybody's out of work or scared of losing their job. The dollar buys a nickel's worth, banks are going bust, shopkeepers keep a gun under the counter. Punks are running wild in the street and there's nobody anywhere who seems to know what to do, and there's no end to it. We know the air is unfit to breathe and our food is unfit to eat, and we sit watching our TV's while some local newscaster tells us that today we had fifteen homicides and sixty-three violent crimes, as if that's the way it's supposed to be. We know things are bad - worse than bad. They're crazy. It's like everything everywhere is going crazy, so we don't go out anymore. We sit in the house, and slowly the world we are living in is getting smaller, and all we say is, 'Please, at least leave us alone in our living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my TV and my steel-belted radials and I won't say anything. Just leave us alone.' Well, I'm not gonna leave you alone. I want you to get mad! I don't want you to protest. I don't want you to riot - I don't want you to write to your congressman because I wouldn't know what to tell you to write. I don't know what to do about the depression and the inflation and the Russians and the crime in the street. All I know is that first you've got to get mad. You've got to say, 'I'm a HUMAN BEING, God damn it! My life has VALUE!' So I want you to get up now. I want all of you to get up out of your chairs. I want you to get up right now and go to the window. Open it, and stick your head out, and yell, 'I'M AS MAD AS HELL, AND I'M NOT GOING TO TAKE THIS ANYMORE!'

Why the hell is nobody on this show mad as hell? Two seasons now of artists dancing like monkeys before an ever increasing television audience and not one of them is breaking the rules and getting pissed off at being treated like a captive in a zoo? And Jerry Saltz, like some Stockholm Syndrome victim expurgating sensibility in exchange for sympathy for their captors? In the last couple of weeks I’ve taken the time to query artists on their thoughts about the show and I get one of two solid responses. One camp simply doesn’t give a damn because they dismiss it as the same formulaic crap that is Project Runway or Top Chef. They see it as a dismal attempt to put amateurs lacking social graces and borderline personalities in a room together to ‘perform’ for an audience that knows little or nothing about the creative process they are pretending to compete in. The other camp of artists take the position, not of disappointment in the formulaic show or even Jerry Saltz, but rather the pathetic and regressive behavior of people who call themselves artists and yet follow the rules given them explicitly, i.e. the contestants. When contestant aren’t crying over criticism or whining about how hard things are for them, they’re busy gossiping like teenagers about sex or wistfully dreaming of how they’ll spend the next $20,000 bonus for winning that week’s monkey dance.

A part of me watches the show and thinks Andy Warhol is still alive living in a penthouse in Las Vegas producing Work of Art, as yet another cynical gesture intended to tear the last vestiges of art apart at the seams like the defeated Scot, William Wallace was drawn and quartered. Never before was Woody Allen so prescient when he said, “Life doesn't imitate art, it imitates bad television.” And that’s why Work of Art is actually dangerous. As the historian Kenneth Clarke said at the opening of Civilisation, “great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts. The book of their deeds, the book of their words and the book of their art. Not one of these books can be understood unless you read the two others. But of the three, the only trustworthy one is the last.” And therein lies the broken promise of the show and the damaging deceit it carries out — that art in America, in the 21st century is nothing more than a series of clever skits, designed by the cynical and carried out by the greedy. With each successive week of Work of Art, season two, we see the producers throw more and more money at the artists as an incentive to perform as if all that matters is fame and cash, and of course that is the only way to achieve great art. The allure is great as we live in a society ever more divided along lines of economic strata. The rich do indeed get richer—much, much richer and believing in the American myth leaves one either isolated and adrift from society, fighting an uphill battle against a mighty foe—greed, or succumbing to participation in the belief, we as a nation will only endure and remain strong if we place money at the top of our idealistic pyramid. Work of Art: The Next Great Artist portrays the last bastion of hope for a cultural legacy, art, as nothing more than a device like all others, developed and pursued for riches at the expense of anyone else who stands in the way. Work of Art portrays all artists as whores, who think they can cleverly bend the rules, convincing the elite they have produced something truly sustaining and enriching in the hopes of making a fast buck. We no longer glorify our gods, our emperors or science, we only glorify money.

Some of you will say, but who cares about a silly television show only a small demographic of American’s will watch. Why does it matter? To me it matters because it is a symptom of something larger and in this case that symptom is in my own backyard. I suppose if I were a chef or a fashion designer, I would have already written about these appalling shows, but Work of Art deals with my profession—art making. More importantly it matters because we can do better and succumbing to this nonsense makes us all complicit, even if we don’t watch. Saltz has at least 5,000 Facebook friends and he writes a column on art in a populist magazine, New York Magazine, and now he’s on television. In other words, he influences popular culture, much more than he cares to admit. This has a trickle down effect on all of us in the same way that bad design does. Accepting silly gamesmanship and mediocrity as art and playing that back to a larger audience, largely ignorant about art, is negligent and narcissism. As mentioned, Jerry Saltz and Bill Powers have both commented on how they participate in the hopes of making art accessible to a larger audience. I maintain, that a larger audience experiences art, fine art (for lack of a better term), by way of indirect exposure. Just try to imagine how much influence Picasso has had on popular culture in the last one hundred years and the closest thing he ever came to making what you could call “pop” was a series of ceramic plates. He is however, a household name, even among the great uninitiated masses and rightfully so. He foresaw the conceptual dynamics of quantum physics before it was put to mathematical formula and his sense of fragmented, folded space has changed the way we interact with things from iPod’s to clothes. We accept a looser organization of things more easily now because of the huge impact Picasso had on society. Art does not need to be, nor in many cases should it be, more accessible to a larger audience. That is the Pandora’s box Warhol opened when he shifted art away from making to making money.

I was saddened frankly to watch an established artist who calls himself “The Sucklord,” kowtow to the judges and diminish his own creative abilities in the hopes of self promotion and a quick buck. Artists on the show are punished for not working outside of their own oeuvre, and yet, presumably that is how they managed to be selected for the show. This reeks of typical art-school crits, where tenured professors sit in judgement of burgeoning artists and fearful of their own tenuous grasp on the art world, pour vitriol and disdain on another’s creative expression. Work of Art also reinforces terrible stereotypes: the art school girl, the art slut, the freak, the redneck self-taught artist, the euro-trash artist and on it goes. Place can be paramount in an artist’s work and throwing an Arkansan into the mix with seasoned kids from New York and LA is simply throwing the proverbial Christian to the lions. In both seasons of Work of Art contestants hailing from rural towns are akin to blacks in horror films—sacrificial lambs. Asking a painter to make something of a gutted Fiat’s parts, proves nothing about that artists’ ability, other than their ability to perform like a trained seal. Art at its core is subversive, dangerous and guileful because it asks questions that most people would rather leave unasked. Its power lies in its truth. Not some ultimate truth, but the truth that we are all better off when we question the status quo and we understand the rational is inextricably connected to the irrational. Work that leaves you bewildered, stunned, shocked and questioning is always the best art. Art that is mystifying and misunderstood in its own time is usually the most important in the long term. As long as the artists on Work of Art continue to play by the rules, the title of the show will remain the ironic joke it is. As Dave Hickey has said; “If there is no art, no culture, then what the fuck are we going to talk about? These are our stories and our stories are all we got!”

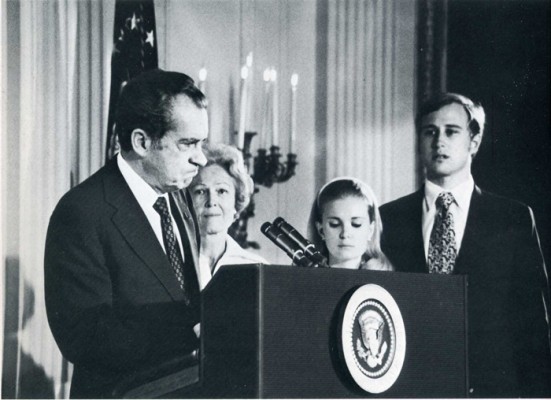

I am a child of Watergate. When I was in grade school in the 1970’s it was an all consuming subject, even among eleven and twelve year olds. My small town high school library made sure there was a special reserve section that dealt with the issues surrounding the continuing unfolding of the scandal and eventual disgraceful resignation of a president of the United States. As a adolescent the idea that a president would not only lie but manipulate the infrastructure of the U.S. government to win re-election was nearly impossible to swallow. My parents were products of the post WW II boom. They went to college to gain teaching degrees which our government paid for in order to promote a more robust democracy in the wake of the atrocities of fascism. It was a time of relative idealism despite the assignation of John F. Kennedy just three months after my birth and later Martin Luther King and his brother Bobby. It was a time of hope despite the insipid bombing of Cambodia, the knifing of a young man at Altamont during a Rolling Stones concert and the hideous plague rained down from the Manson family in L.A. The remnants of 1950’s America was still holding charge in small town America. I was taught even then, at that early age about civics, citizenry and the idea of a functional government. My father voted for Nixon, twice and my mother voted first for Humphrey than McGovern, but I was taught to respect differences because the vote is what enabled reconciliation. Republican government with democratic underpinnings was the greatest form of government known on Earth, and despite it’s faults, it was to be respected.

I am a child of Watergate. When I was in grade school in the 1970’s it was an all consuming subject, even among eleven and twelve year olds. My small town high school library made sure there was a special reserve section that dealt with the issues surrounding the continuing unfolding of the scandal and eventual disgraceful resignation of a president of the United States. As a adolescent the idea that a president would not only lie but manipulate the infrastructure of the U.S. government to win re-election was nearly impossible to swallow. My parents were products of the post WW II boom. They went to college to gain teaching degrees which our government paid for in order to promote a more robust democracy in the wake of the atrocities of fascism. It was a time of relative idealism despite the assignation of John F. Kennedy just three months after my birth and later Martin Luther King and his brother Bobby. It was a time of hope despite the insipid bombing of Cambodia, the knifing of a young man at Altamont during a Rolling Stones concert and the hideous plague rained down from the Manson family in L.A. The remnants of 1950’s America was still holding charge in small town America. I was taught even then, at that early age about civics, citizenry and the idea of a functional government. My father voted for Nixon, twice and my mother voted first for Humphrey than McGovern, but I was taught to respect differences because the vote is what enabled reconciliation. Republican government with democratic underpinnings was the greatest form of government known on Earth, and despite it’s faults, it was to be respected. True Detective and the second season of House of Cards act as agreements in an argument with no contradictions. These dramas about police work in the heart of Louisiana and the machinations of our central government in Washington, DC, accept bleakness as religious doctrine. Both shows a denuded moral landscape so tangible it is like smelling a peach at the apex of its ripeness on a hot summer day. The fine art world, if we can any longer call it that, has remitted a similar ripe oblivion but exhibits it in a way largely inaccessible by the average American, let alone any real admirer of art. Matthew Barney’s latest plethora of shit (literally) filmic opera promises a more esoteric rendering of the aforementioned television dramas. But few will ever see Barney’s high fashion elitist rendition of scatalogical infinity, but many will see House of Cards and True Detective. The new dramas hint back to the fears of the 1970’s (nuclear war, the beginning of the AIDs plague, sexism, and government corruption from the top down) but instead offer a new outpost in post-postmodern explication that insists we should all make peace with the fact that all is lost, rather than remain firmly connected to any remnant of hope. At least, dare I say, there were rafts one could reach out for in the river of shit of the 1970’s. What make these new dramas even harder to digest is the fact that they are so profoundly well acted and written. There is no wink or nod to McLuhan’s Bonanza Land, as in David Milch’s magnificent Deadwood. House of Cards 2 and True Detective forego the Shakespearean rhetoric and ode to westerns in favor a unannounced punch in the nose. Thank you sir, may I have another.

True Detective and the second season of House of Cards act as agreements in an argument with no contradictions. These dramas about police work in the heart of Louisiana and the machinations of our central government in Washington, DC, accept bleakness as religious doctrine. Both shows a denuded moral landscape so tangible it is like smelling a peach at the apex of its ripeness on a hot summer day. The fine art world, if we can any longer call it that, has remitted a similar ripe oblivion but exhibits it in a way largely inaccessible by the average American, let alone any real admirer of art. Matthew Barney’s latest plethora of shit (literally) filmic opera promises a more esoteric rendering of the aforementioned television dramas. But few will ever see Barney’s high fashion elitist rendition of scatalogical infinity, but many will see House of Cards and True Detective. The new dramas hint back to the fears of the 1970’s (nuclear war, the beginning of the AIDs plague, sexism, and government corruption from the top down) but instead offer a new outpost in post-postmodern explication that insists we should all make peace with the fact that all is lost, rather than remain firmly connected to any remnant of hope. At least, dare I say, there were rafts one could reach out for in the river of shit of the 1970’s. What make these new dramas even harder to digest is the fact that they are so profoundly well acted and written. There is no wink or nod to McLuhan’s Bonanza Land, as in David Milch’s magnificent Deadwood. House of Cards 2 and True Detective forego the Shakespearean rhetoric and ode to westerns in favor a unannounced punch in the nose. Thank you sir, may I have another. Maybe what bothers me most about all this acceptance of corruption, hate, violence, darkness and sexual malaise is the complacency around it. More than affecting a new kind of awareness, a call to arms that we should all recognize something is terribly amiss about our culture ala Network (1976), we are left alone in the dark to contemplate time being a “flat circle”. True Detective in particular acts as a model for the two extremes that represent themselves in modern America. On the one had we have the greatest increase in religious extremism and fundamentalism in our history, and on the other, the unraveling of time/space with the discovery of the Higgs Boson. I should be celebrating M-theory being used as an expository monologue in American mainstream television, but instead it just makes me sad. To hear Matthew McConaughey recite multiverse theory and superimposition betrays it the wonder it deserves despite his lilting Texas accent. Pizzolatto’s message is clear, we’re all rodents on an endless treadmill doomed to repeat ourselves. Similarly, Francis Underwood, played by the extraordinary Kevin Spacey (who reminds me there is still hope for acting after the death of PSH) has a similar take on time/space, except that his is beholding to only one ideal—power. For the Underwoods as DC power couple, even rape can be turned into a power grab ratings gambit. Even Camille Paglia blushes at Claire Underwoods coldness and calculation.

Maybe what bothers me most about all this acceptance of corruption, hate, violence, darkness and sexual malaise is the complacency around it. More than affecting a new kind of awareness, a call to arms that we should all recognize something is terribly amiss about our culture ala Network (1976), we are left alone in the dark to contemplate time being a “flat circle”. True Detective in particular acts as a model for the two extremes that represent themselves in modern America. On the one had we have the greatest increase in religious extremism and fundamentalism in our history, and on the other, the unraveling of time/space with the discovery of the Higgs Boson. I should be celebrating M-theory being used as an expository monologue in American mainstream television, but instead it just makes me sad. To hear Matthew McConaughey recite multiverse theory and superimposition betrays it the wonder it deserves despite his lilting Texas accent. Pizzolatto’s message is clear, we’re all rodents on an endless treadmill doomed to repeat ourselves. Similarly, Francis Underwood, played by the extraordinary Kevin Spacey (who reminds me there is still hope for acting after the death of PSH) has a similar take on time/space, except that his is beholding to only one ideal—power. For the Underwoods as DC power couple, even rape can be turned into a power grab ratings gambit. Even Camille Paglia blushes at Claire Underwoods coldness and calculation.