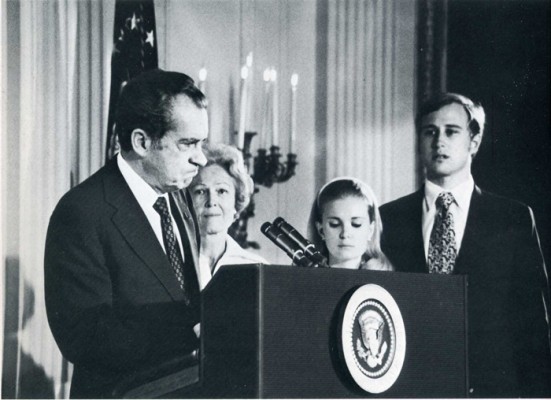

Departure

Dan: I'm older, and I'm much less friendly to fuckin' change. Al Swearengen: Change ain't lookin' for friends. Change calls the tune we dance to.

—Deadwood

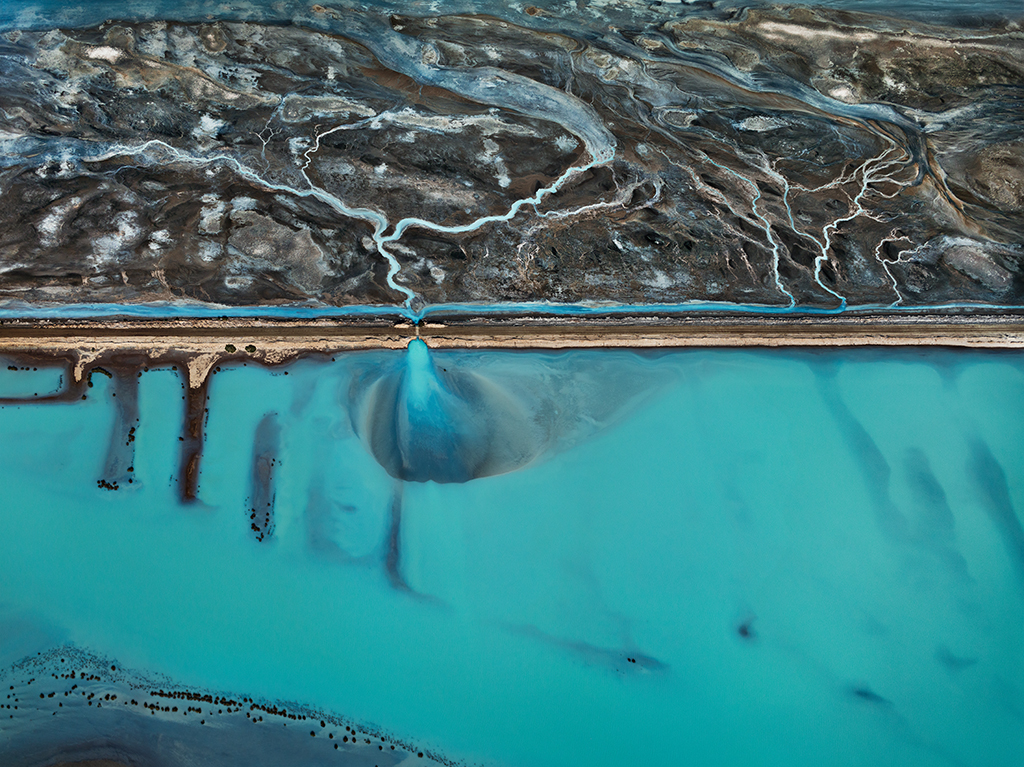

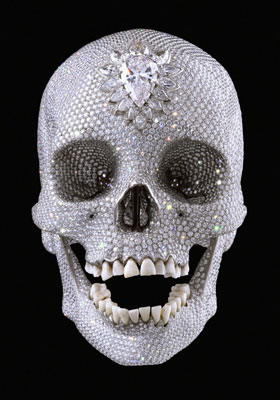

The efficacy of life is held within the grip of memory. Without memory we and indeed everyone we know or have known do not exist. We spend our lives fighting against loss which is primarily fighting against the loss of memory. We manifest things—art, to hold onto the world which we live in. It is within this contentious dance with death that we manifest life.

The tenuous dialogue between memory and existence has grown even more difficult in the digital age. Ideas constructed within the macro world of paint, stone and pencil become much more liminal in the world of bits and bytes. Not only do we struggle with the relationship to digital art in how it’s displayed—computer monitors, televisions—but its preservation and continuation. Since the 1970’s the platform for music has gone from vinyl to 8-track to cassettes to compact discs to purely digital storage and now, back again to vinyl. How is an artist to predict the format which will hold the memories and expressions of tomorrow? Who now owns a betamax machine or a cassette player? As difficult as it is to sell works of art on paper, vinyl or canvas, it becomes even harder to make a living from digital production. As we’ve witnessed with the near death of newspapers and the implosion of the record industry, digital media lacks the tactile semi-permanence of something hanging on your wall. A Bill Viola work requires a monitor whose own technology is shifting every year. Televisions have gone from cathode ray technology to LED in just a few decades. Imagine how we will view our digital creations in 20, 30 or 50 years from now.

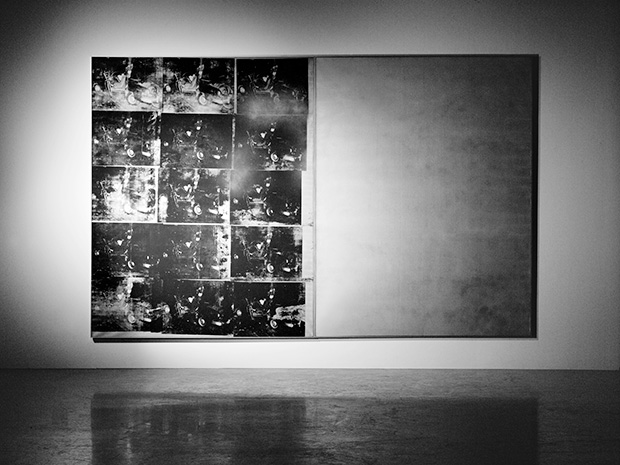

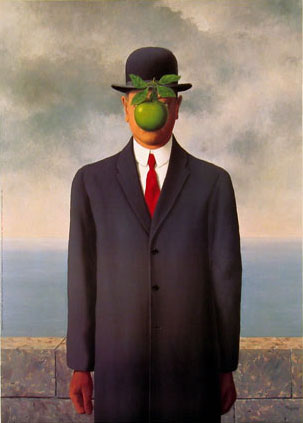

What I’ve come to realize however, is that none of this matters. The act of creation must go beyond the desire to hold on and the need for remembering if it is to become universal. The work of Bill Viola isn’t dependent upon a television monitor, it’s dependent upon the themes of being human. One could imagine his work being acted out live or drawn as a graphic novel or written out as a poem. It is the works of art which transcend the grip of memory that ironically live on the longest in our collective recollections and cultural identity. Loss is a starting point not an ending. When we loose someone important to us we don’t also kill ourselves, despite the anguish and sorrow we feel. We inherently understand that living is the point even if we understand very little about how that actually comes to be or why it is we too will eventually die. The 1953 work Erased de Kooning Drawing by Robert Rauschenberg is a testament to the way art can transcend the confines of memory and become something else, something universal. It doesn’t matter if you’ve ever seen a de Kooning before or even if you know who de Kooning was and his importance in the art world. It is enough to understand that one artist erased the work of another. The act of destruction becomes an act of creation.

This year has seemingly become a meditation on death, loss, and memory in my life. Mortality took up a seat next to me in my favorite pub and asked me to buy her a drink. I didn’t invite her to sit next to me and frankly before a couple of years ago I didn’t even know her name let alone hang out with her, and yet here she is, now a permanent fixture on that bar stool. My resistance was, at first swift, because like everyone else, I saw death as a threat to life, a destroyer of memories. Her presence there, forced me to confront entropy in a way that I had always pretended to embrace and understand, but suddenly realized was a pretense. I had disguised fear in a cloak of creativity. Life it turns out is much more like Schrödinger's cat experiment than even I had cared to admit.

Memories are not a box of photographs or a fleeting glimpse in our minds of a time we lived in the past. They are biochemical constructs built from electrical impulses that are stimulated from interactions in the real world as a tool for navigating the challenges of being. Evolutionarily speaking, memories have aided homo sapiens by providing us the foundation to create analogies, make tools, and catalogue our world. Memory has extended our lifespans and allowed us to surpass all other creatures on earth in terms of our dominance as a species. And the way in which those biochemical impulses are leveraged is through creativity and that creativity works by first assailing the memories we have available to us and then seeing how they can be reconstructed in a new way. The collective memory of de Kooning is now the collective memory of Rauschenberg which is really the collective memory of humanity. The symbolic is the real because we are alive.

The exciting opportunities available in the digital realm are the ones that challenge our understanding of permanence not the ones which reinforce our desire for nostalgia, for remembering and memorial. The creative act is an act of destruction because entropy is a natural component of being alive and to embrace its reality is to embrace being. It is also an impossibility. Matter is a constant in the universe and although it desires a state of equilibrium it is a constant. Staring at the Erased de Kooning Drawing brings us closer to that knowledge of equilibrium and a little closer to understanding the nature of being.

“Everywhere one seeks to produce meaning, to make the world signify, to render it visible. We are not, however, in danger of lacking meaning; quite the contrary, we are gorged with meaning and it is killing us.” ― Jean Baudrillard