Death's Fantasy

“He vaguely desired to walk around and around the body and stare; the impulse of the living to try to read in dead eyes the answer to the Question.” ― Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage

As a little boy living in western New York poised almost exactly between the cities of Rochester and Buffalo I learned my adult sleeplessness. The sleepless nights began sometime around the age of ten or eleven. These were still the days when you had nuclear disaster preparedness drills at school. We were told where to find the bomb shelter in the basement of the school and how to move their in orderly fashion if we heard the air raid siren. An inquisitive and precocious child led to my unending questioning of my world. Every week, usually at night, I would hear the drone of B-52’s flying overhead. I asked my father one day, why the bombers were out flying at that time and where they came from. My father, not being one for sensitivity, immediately responded that they were part of the nuclear defense grid, or strategic air command that flew constantly in shifts carrying nuclear weapons as a deterrent against a Soviet first strike[i]. Right around this same time, my parents became friends with a couple just up the street. The husband worked for FMC or the Food Machinery & Chemical Corporation in nearby Lockport, NY. He, lets call him David, was employed as a geneticist researching new techniques to increase crop production. One night while eavesdropping at the top of the stairs, I heard David say, “if there was an explosion at the FMC plant, all of western New York would be wiped out.” The train that carried FMC petrochemicals traveled right through our small town and upon hearing the train I would lay awake in a soft panic hoping the train did not derail. Perhaps this is how DeLillo’s White Noise was born. So, between the nuclear threat in Niagara Falls, and the chemical threat in Lockport, not to mention the research on nuclear fusion taking place in Rochester, I lay awake at night a lot.

During this same time, the artists Ed and Nancy Reddin Keinholtz created Still Live (1974). The art was a work of theater where the viewer became the actor in something very real. The Keinholz’s built a set piece of a typical American living room and surrounded it by barricades and barbed wire. Before entering you were asked, essentially, to sign your life away, in effect liberating the exhibition or artist of any responsibility should something go horribly wrong.

I the undersigned am at least 18 years of age. I fully and soberly understand the danger to me upon entry of this environment. I hereby absolve the artist Edward Kienholz, the owner of the piece and the sponsors of this exhibition of any and all responsibility (morally and legally) on my behalf.[ii]

The reason for signing such a disclaimer was due to the high caliber rifle perched above the television in the living room set the Keinholz’s created, which was aimed directly at the chair in facing it. Allegedly (this was never verified) a black box controlled a random timer connected to the rifle’s trigger that could fire a live round at any time over the course of one hundred years. The Vietnam War was winding down but the country had endured more than a decade of war in southeast Asia with the networks carrying a scrolling list of the American dead, night after night during that time to the tune of 58,282. [youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8YCNFmWtYU&w=640&h=480] The Keinholz’s forced violence from the virtual space it occupied for most Americans watching television to the real, by confronting them with the possibility of a very real death. In September 1974, Nixon had just resigned over the Watergate Scandal and the Symbionese Liberation Army had kidnapped Patty Hearst. IRA bombings were on the rise in London and fighting persisted in the Golan Heights of Israel. Inflation was on the rise with a deep recession unfolding across the country. This was the time of ‘generic’ foods and long gas lines. In the midst of this, Ed and Nancy Keinholz placed a work of art in the center of Berlin that directly threatened the viewer. Their goal was to deliberately disrupt and rupture the passivity Americans held toward violence and their complicity in it. “Keinholz’ theatricality was meant to heighten his critique of aspects of American society, and he attempted to construct situations in which the everyday became visible for his viewers to question and ponder—to create opportunities aimed at effecting significant change in behavior.”[iii] The Kienholz’s were interested in revealing the everyday persistence of violence and our incorporation of it as commonplace. An earlier piece The Beanery (1965) based on a Hollywood bar he used to frequent, the viewer walks past a stack of newspapers that read “Children Kill Children in Vietnam Riots” before entering the bar. Ed Kienholz’s confrontational perspective, later shared in collaboration with his wife, focused on shaking people loose from their dream state and forcing confrontation with the system they supported. Ed Kienholz said;

It is my contention that to the extent that the major networks intertwine, we, the viewing public, are endangered...In my thinking, prime time should be understood as the individual span each of us has left to live here on earth. It’s a short, short interval and serves the best quality possible. Certainly better than the boob tube pap we all permit in the name of bigger corporate profits and free enterprise.[iv]

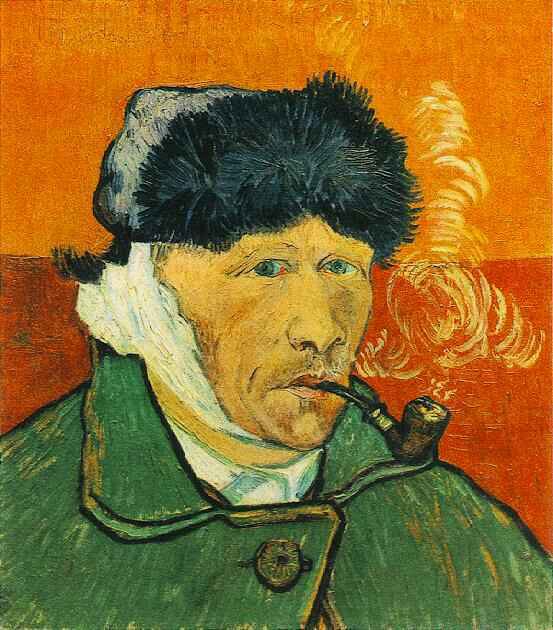

It is hard now to recall the extraordinary violence of the time. I’m sure my sleepless nights were exacerbated by watching the CBS Nightly News with Walter Cronkite night after night and witnessing the scrolling lists of Americans killed in the conflict. In fact, another piece by Kienholz titled The Eleventh Hour Final (1968) speaks directly to that experience, with a death list permanently painted on a TV screen that reveals a decapitated mannequin head staring back at the viewer from inside the set. The 70’s was a time of fear, uncertainty and fractured psyche in America. I remember distinctly feeling a deep sense of loss and anxiety, even at 11 over Watergate. I had been raised to believe in the Constitution and our government as essentially functioning, despite their imperfections. In 1969 I watched the moon landing and found the hopefulness of science conquering our deepest problems. By 1974, Watergate was unraveling our government, the recession hit, crime was rising and we encountered defeat in Vietnam by a low-tech insurgency. In the midst of all of this was the ever looming threat of nuclear holocaust and biological warfare. The pantheon of American cinema during the 1970’s was filled with darkness from Andromeda Strain to Twilight’s Last Gleaming reinforcing what must have seemed at the time like a real threat of armageddon, not the phony Walking Dead gorefest on TV now.

Unfortunately, the Keinholz’s Still Live was even too intense for its German audience. German authorities rapidly shut down the exhibition and arrested Ed Kienholz on “unauthorized possession of arms” and “the suspicion, of a conditional, but intentionally attempted homicide.”[v] The piece was bizarrely rescued along with an intervention on Kienholz’s behalf by the American Consulate and relocated to Switzerland before the tableau was shipped back to the States in a crate and stored until 1982. It was briefly exhibited at the now defunct, Braunstein Gallery in San Francisco and then returned to its crate where it remains today in the possession of Nancy Kienholz.

Americans are not fond of self-deprecation or self-criticism. We like to think we are know it alls, who have all the answers and don’t need anyone, even our own calling us out on our shortcomings or bad behavior. Ever since Jimmy Carter said, “In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does but by what one owns." in his sweater in his fireside chat in 1979, we have reacted violently against any form of reality. Kienholz’s dream of threatening Americans into confrontation with their violent, sexist, racist and classist ways disappeared when Ronald Reagan was elected president. On that day, Americans firmly rejected compassion and sensibility with the delusion of the American dream. The theatrics and conceptual groundings of 60’s and 70’s art was replaced with the blinding irony of the 80’s.

So today we find ourselves immersed in a world of corporate politics where our dreams have been replaced by consumerism and our productivity and inventiveness shipped offshore in favor of the sad theatrics of reality TV. The darkness of the 70’s, which was always couched in Kienholz’s idea of real threat has been replaced by fantasy threats—zombies and vampires. The art world has matched with its own kind of fantasia, selling its soul to the highest bidder in order to provide religiosity to hedge fund managers, or as the late Robert Hughes put it, "The new job of art is to sit on the wall and get more expensive." There are a few artists who continue to push the the ideas that the Kienholz’s instigated in those heady decades of the 60’s and 70’s, like Gregory Green and Wafaa Bilal, or Banksy, but the art institutions marginalize them. In the early nineties I had the pleasure of working briefly with Gregory Green in NYC delivering art and then visited an opening of his at the Dart Gallery in Chicago where I lived at the time. Gregory had a wonderful piece he installed there called Thirty Blade Wall Installation. He had directly mounted thirty circular saw blades on their own axels and they spun away in magnificent danger, free of any protective covering or roped off quadrant. Anyone could have simply reached in and watched their fingers fly effortless about the room in wondrous horror. Green had made a more minimalist and direct homage to the Kienholz’s and I remember being very moved by the piece.

It is important that we remain connected to the effects of violence and their aftermath if we hope emerge from the lessons of the 20th century intact. Our current obsessions are not idiopathic, but firmly couched in our inability to contend with our own past. We have never reconciled the deceit of Watergate or the trauma of Vietnam. It is no accident the 9/11 memorial is an inversion, a conceptual black hole that swallows both the living and the dead from that moment in time. It is an astounding representation of national shame that looks not toward reconciliation, empathy and hope, but toward an ever darkening cynicism and irony. After the trauma of 9/11 one could presume the nation would grow more empathic, more sensitive to the needs of others, as was witnessed in NYC in the weeks after the event. Unfortunately, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index that has been running since 1979 suggests quite the contrary. The 2011 study results found, “almost 75 percent of students today rate themselves as less empathic than the average student 30 years ago.”[vi] There are certainly many contributing factors to this finding but one can’t help but think that ‘magical thinking’ is a leading contender. As a nation we seem consumed by it, otherwise how could one explain the dramatic reversal away from a solid middle class? Four hundred Americans now hold as much wealth as half of our entire population.[vii] And yet, the battle rages on against the poor. A key point in the Kienholz’s work is Ed Kienholz’s insistence on placing himself as an implicit participant in their own commentary and criticisms. Barney’s Beanery was a bar Ed frequented and he was the first to sit in front of the rifle in Still Live. His anger was directed as much at himself as it was at our collective passivity. He once took an axe to a desk at TWA as result of the airline’s disregard toward the mishandling of a Tiffany lamp Kienholz had shipped with them. He put himself firmly in the tableau, risking arrest and contempt to make an artistic gesture.

The interest in post-apocalyptic fantasies and immortality represented by the plethora of vampire and zombie movies, books and television shows is a desperate form of escapism for a country who has lost its sense of empowerment. If only we had heeded the words of Carter in 79’ and learned to begin using less and stop striving for more we might be closer to a true triple bottom line capitalism now. We might also have a more robust and meaningful culture, less interested in heroics and life after death scenarios and more involved with the real. I have written before on Francis Bacon’s rejection by many of the American art critics and I think the same could largely be said for the Kienholz’s. Ed and Nancy Kienholz’s form of intimidating and even angry art-making was sidelined and diminished by a market that preferred the promise of the sublime over the delivery of truth. Of course there is no absolute truth, but as with science, art at its best is interested in asking questions that can uncover a deeper sense of ourselves and our place in this world. In so doing, it reminds us of our interconnectedness and the fact that violence has consequences, like the rifle pointed at us from above the TV. We can only lay prostrate before the television, computer monitor or smartphone for so long before our own actions catch up to us and we realize that our fantasies have become nightmares, just like the ones I had as a boy.

[i] After a fair amount of research, despite B-52’s being housed at Niagara Falls International Air Field, I could find no evidence that nuclear warheads were involved. BOMARC defense missiles were stationed there until 1969 and may have carried a nuclear payload, but the air base was primarily a fighter base. The air bases with Strategic Air Command nuke’s were located in Rome and Plattsburg. In reality, during that paranoid time, it is hard to say what was housed in Niagara Falls. It was supposedly ranked 45th as a possible nuclear strike target, which given the scale would have unquestionably wiped out southern Ontario and Western New York.

[ii] Kienholz, Edward. Edward Kienholz: Still Live: Aktionen der Avantgarde, Projekt für ADA2. Berlin: Neuer

Berliner Kunstverein, 1975, n.p.

[iii] Willick, Damon. “Still Live.” In Art Lies, No. 60, Winter 2008, p. 23.

[iv] Ibid, p. 26.

[v] Kienholz, Edward. Edward Kienholz: Still Live: Aktionen der Avantgarde, Projekt für ADA2. Berlin: Neuer

Berliner Kunstverein, 1975, n.p.