Manifestos and Madness

“Mama always told me not to look into the eye's of the sunBut mama, that's where the fun is” —Blinded by the Light, Bruce Springsteen

10. We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice. —F. T. Marinetti, The Futurist Manifesto (1909)

In the recent issue of Harpers Magazine an article by T. M. Luhrmann focuses on how the Christian Hippie movement of the sixties became the evangelical right of today. It was both mesmerizing and enlightening to read about this recondite subject that so few have researched. We have a strong tendency as Americans to wish for expeditious answers and ignore the deeper meaning and history behind things. To discover the Jesus Christ Superstar of my youth, that even I, a devote atheist, found inspiring, was the underpinning of much of what Democrats today despise, was nothing short of revelatory. It occurred to me, however, that we are wired for such things be it religion, art, science, etc.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvVr2uks0C8]

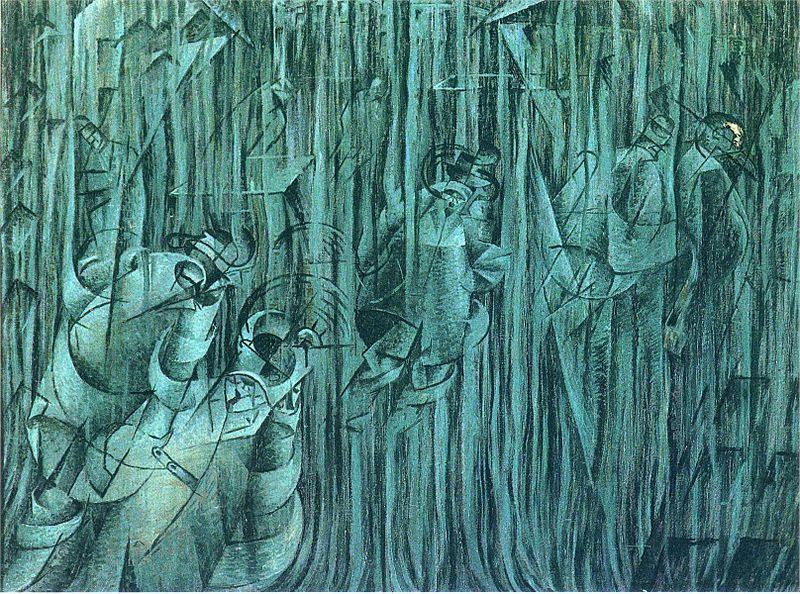

In 1909 a young radical named Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote the Futuristic Manifesto. That same year Nicola Tesla had presciently predicted our current wireless network we are so desperately dependent on, Ernest Shackleton had nearly died visiting the south pole and the fragmented sub-cultures of Europe were stirring with resentment toward empire. It is a compelling bookend to the denouement that was the sixties. The flower children, hippies and the Summer of Love actually set the stage for todays right wing radicalism as a bookend to Marinetti’s embrace of Futurism.

Luhrmann eloquently describes his investigation revealed the children of devote Catholics and Protestants who loved God, country and JFK bore the fruit of the evangelical, privileged class of the right-wing today. Hippies drawn to hallucinogens and free love in order to escape the confines of modernity found themselves pulled toward the security of big church love and a need to belong outside of addiction, filth and disillusion lay the open arms of evangelicals and a different, more structured religious belief. In effect this is absolutely the same thing that has happened in art throughout time. The ebb and flow of radical vision gives way to reactionary responses that reinforce accepted forms of creating. The late Thomas Kinkade, the so-called ‘painter of light’ was the most successful and popular artist in America over the past twenty years. Kinkade, just like the Futurists, leveraged a popular mythos to express a dogma, in his case a Christian ethos. Americans sacrificed critical thinking for wealth, which in turn they were denied by the elite. As Robert Hughes said of Jeff Koons,

“If cheap cookie jars could become treasures in the 1980s, then how much more the work of the very egregious Jeff Koons, a former bond trader, whose ambitions took him right through kitsch and out the other side into a vulgarity so syrupy, gross, and numbing, that collectors felt challenged by it.”

It is a parallel reflection of our inability to step back from the edge and accept the uncertainty of not-knowing. We want, damn it, we demand certainty in our society. We hold smart phones that provide instant answers, drive cars connected to satellites hovering in orbit 22,000 miles above our heads yet lubricated by a fluid born from the detritus of millions of years ago. It is no wonder we live in an age of fracture, of a potential universal schizophrenia. Marinetti and his fellow Futurists rang the warning bell of this ideation in 1909! Of course, Marinetti himself avoided the outcomes of his belief but many of his fellow Futurists fell pray to it, dying as a result of horrors of trench warfare.

Whether art, religion or science the key to enlightenment is ones ability to come back from the edge of radical experience. Science is now reaching the same boundaries of truth as all dogmas before it. Cosmologists like Leonard Susskind question the idea that truth is accessible at all. He has walked to the edge of reality and he has stepped back. This is closer to the methodology native cultures of the Amazon basin use to accept the complexities of our world. It is a fair analogy. Although, Amazonian basin tribes do not carry smart phones or access the internet, they are surrounded by a pharmacopeia that to this day is still little understood by modern medicine and science. Shaman acutely understand the relationship between the frontiers of our own imaginings, understanding and reality and the present. They say ‘plants speak to them directly’ but really mean the ingestion of psychotropics allow access to a knowledge that expands our postmodern understanding of reality. Like the best artists, scientists and devout, they approach the sublime with feet firmly planted on the ground. They do not embrace dogma, but rather the uncertainty of our world and in so doing they scrape against a kind of truth.

“If you can approach the world's complexities, both its glories and its horrors, with an attitude of humble curiosity, acknowledging that however deeply you have seen, you have only scratched the surface, you will find worlds within worlds, beauties you could not heretofore imagine, and your own mundane preoccupations will shrink to proper size, not all that important in the greater scheme of things.” ― Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon

For those hippie, Jesus-freaks turned right-wing evangelicals, the psychotropics ingestion of the sixties was a result of psychological loss. They discontent from the mainstream culture was not as it would seem a matter of direct denial of its efficacy, but rather more psychologically bound in its adherence to sociological structures that disrupted acceptance. If you’ve watched the show Mad Men then you understand this reaction. 1950’s America was a reaction to the simultaneous hubris of winning a war that we had little to do with (compared to Europe or Asia) and left America wealthier than it deserved due to its bounty of industrial resources. It was denial of death (as opposed to the Futurists) and an embrace of immortality (realized the in the dogma of corporate culture). Beware the manifesto, the embrace of certainties, liberal, conservative or otherwise as it only leads to a society of judgement, and absolution.