Ontology of the Sublime

“The question that now arises is how if we are living in a time without legend or mythos that can be called sublime, if we refuse to admit any exaltation in pure relations, if we refuse to live in the abstract, how can we be creating a sublime art?” —Barnett Newman

I’ve been considering the sublime a lot lately. This concept of observation that invokes awe. I recently completed Ross King’s book Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling, an excellent, and detailed account of the painting of the Sistine Chapel that took the artists from 1508 to 1512 to complete. During the celebration of All Saints Day, that October 31st, 1512 when the ceiling was finally unveiled in its entirety, did the cardinals, attendants, dignitaries and indeed Pope Julius II himself, look up at Michelangelo Buonarroti’s ceiling and find it sublime as many of us do today? I ask this question because it appears, that for all practical purposes, as Barnett Newman said in the 1960’s, that we have lost our ability to create the sublime.

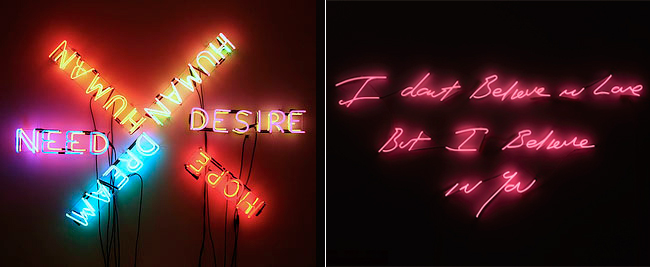

Sublime is something altogether different. Sublime, I believe requires abstraction, as Newman said. By this I mean using our imaginations in combination with our knowledge and experience to construct manifestations of what we observe beyond the simplicity of what are eyes are telling us (or any of the other senses for that matter.) Newman’s presumption, that we have lacked since the sixties this ability to abstract, might be argued in much of what is found in galleries and museums today. It would appear an ability to abstract is preventing us from producing, and in turn observing much that could be considered the sublime in art. However, I find myself surprisingly in disagreement with Newman’s comment, despite seeming overwhelming evidence to the contrary. I believe our capacity for abstraction has never been greater in human history and we are simply living in a natural in-between art state. A state that is percolating old ideas and mashing them against our current circumstances until we re-imagine the profound, the sublime, in a new way.

Here we are where one out of every seven people globally owns a smartphone and two-thirds of the planet has at least a mobile phone. Google’s search engine processes 24 petabytes (24m gigabytes) of data a day. We have sequenced the entire human genome. We have sent a probe beyond our universe and landed multiple crafts on Mars now roaming its surface, sending back data. We can look up any snippet of information in less than a quarter of second. We have looked back into time/space with telescopes to the edge of the Big Bang and visited the deepest ocean trench in the world. On the surface it appears this enormous amount of data is overwhelming us, rendering us not in awe but in a state of complacency. Much of the art being sold commercially and displayed in museums is recycling ironic gestures like a turgid whirlpool of endless self-referencing banality. The art world remains largely and firmly planted in traditions that no longer comment on our current reality let alone re-imagine a future one. “Art is either plagiarism or revolution” as Gauguin said, and today we are seeing a great deal of plagiarism, but I believe that is not cause for alarm. I think we are experiencing another fallow time in the history of art, similar to the Middle Ages in Europe, but on a much more compressed scale.

The Renaissance was a time of concentrated wealth whose expression was quantified in expanding culture based on classical ideas found in ancient Greece and the Roman empire. Although a time of corruption, war, plague and pestilence it was also a time of growing science and technology. Religion, not technology formed the center of the growth in the European Renaissance and indeed supplied the wealth that provided for much of the greatness that lasts today in terms of artistic production. Julius II commissioned extraordinary artists (considered great craftsmen at the time) such as Michelangelo and Raphael. There were vast numbers of ignorant people living in relative squalor and then there were the elite who had access not just to better living standards, food and sanitation but knowledge. Michelangelo was well schooled in Latin, the Greek classics, and was carefully tutored in advanced methods of sculpture, fresco, painting and architecture as well as mathematics beginning at 15. He had access to the finest Florentine crafted pigments, some so rare their ingredients came as far away as Iran and cost their weight in gold. Michelangelo might not have had cell phones and the internet, but he had that periods equivalent. His assistants in the making of the ceiling were the finest in Europe, all masters in their craft and knowledge in their own right. So, then as now, a great separation existed between the have and the have nots, between technology and ignorance. It is precisely out this sort of mixture that great art is born.

We are emerging from a brief middle ages of culture, where the clock was briefly turned back out of ignorance fear and mostly out of greed. But from the ashes of that fading, impotent ideology, will emerge a new generation of artists who were born into the dynamics of our technologically centric world. This new generation of artists will circumvent old ideas directly by leveraging the technology that is second nature to them. Ideas on communication, human interaction, perception and even the very nature of reality will be upended and greatness will be born. The ironic loop is one of diminishing returns and we have yet to experience the full measure of art in the 21st century and with it new forms of sublime. As Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe said in his book, Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime;

Technology is produced by capitalism in order to consolidate and extend capitalism’s interest, which include the latter’s constant transformation, because capitalism’s persistence depends on its being the source, so that the product is also the producer as thinking is thought’s producer and product. I have suggested that the sublime becomes identified with the idea and image of technology, appears within it and adopts its appearance, at the point where the origin of technology is found in earlier technological functions rather than anything ever done or thought by a human—which is to say, where the technological is seen to have become the origin of, that which makes possible, a kind of thought and a kind of body which wasn’t there before.

When Pope Julius II gazed upon the chapel ceiling during the final reveal by Michelangelo, he was excited and thrilled and he asked for more gold. The Pope did not encounter the sublime that day anymore than he did when he gazed upon the three frescos of Raphael’s in his private chambers. His ego and the context of power would not permit it. Michelangelo may have been the greatest living artist of the time, but he was still a craftsman, and artisan who drafted stories for the masses. The sublime experience was intended for those who came to the chapel for mass, not for those in power. Then, like today, art served in parallel to technological advancement as a gateway to the sublime. The third law of Arthur C. Clarke’s applies then and now, to both art and technology; “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This is precisely why we haven’t yet seen the next generation of great art. Artists need to construct a kind of magic, that will reveal the underpinnings of a deeper knowledge and we will once again experience the sublime. The magic in Michelangelo was in his interpretation of often obscure bible passages and characters using an extremely difficult technique to master combined with some of the finest foreshortening and drafting techniques ever rendered by hand. Imagine painting something into wet plaster (intonaco) with a badger hair brush using pigments that have been hand-ground by monks in Florence on a curved surface 60 feet above the ground and representing perfect perspective in a contorted figure that is twice life size. The intonaco dries within one day, so you can’t paint the figure all at once but must break it into Giornate’s (the famous figure of Adam on the ceiling took just four.) That would indeed seem like magic.