My Twombly

My Twombly When I was invited to contribute to this blog and asked to write, as my first assignment, a personal epilogue to the recently ended life and career of Cy Twombly, I questioned whether my own knowledge of the artist and his work was sufficient to construct even a modest statement of informed inquiry. Should I first dust off my undergraduate bibles for a refresher course in classical mythology and the relics of antiquity? Must one have studied semiotics, become fluent in Lacan, made the pilgrimage to Roland Barthes, and met Clement Greenberg at the crossroads of aesthetics and apotheosis before taking that fatal turn toward Derrida? How far down the rabbit hole of academia must one go in order gain a firm foothold on Twombly? Into what thicket of intellectual discourse must one tread? Of course, perpendicular to this very question runs another: why does work so often described as child-like attract such intellectual admiration from theorists and artists alike? It is perhaps because Twombly was, after all, a painter who imbued his work with labyrinths of allusion to poetry, philosophy, and history which, while not allegorical, nonetheless spun myriad opportunities for meta-synchronous reference and trans-historical dialogue.

Consider, for example, Twombly’s “Apollo and the Artist” (1975).

Whether we engage with the painting before knowing its title or vice versa, we know we must search our memory for who and what was Apollo. There are, of course, not one Apollo but many: the Dorian Apollo, the Minoan, the Anatolian, yet it is the Delphic Apollo with which we are most familiar, the prophetic deity attending the Oracle of Delphi who presided over medicine, healing, arts, poetry, music, and much else. Hermes, from whom we have the term hermeneutics, the process of discovery and interpolation, created for Apollo the lyre, the musical instrument (associate muse-ical and museum) to accompany lyrical hymns of poetry.

The use of palimpsest so prominent in Twombly’s artwork draws convenient metaphor to the artist’s retreat in 1957 (which also marked the closing of the Black Mountain College where he studied) away from emerging American postwar consumerism to Italy where ancient art and relic still stood as icons of a classical Arcadia. In Rome, Twombly’s abstract expressionist style grew modernist roots into the cracked foundation of European past.

Returning to the painting, we may think we recognize allusive clues: Mediterranean blues (Twombly identified himself as a Mediterranean painter), a musical clef symbol, a laurel branch. But a search for symbolism, in Twombly’s pictures will go only so far before the viewer is pulled under the surface of familiarity into a watery world where the signifier of language retains its intonation but is dislodged from signified meaning, like the voice of Charlie Brown’s school teacher whose muffled unintelligible speech is not unlike a voice heard through a wall, or underwater. We can explore “Apollo and the Artist” as a map; our eyes navigate as they are trained to along the drawn directional arrows, up and across to our own familiar-looking habitat of alphanumeric symbols with arrangements we know and trust. We try continuing along the plane of a sentence toward meaningful conclusion, but suddenly the act of reading is disrupted. Twombly has arranged legible (at least that) numbers and letters alongside scribble marks so approximate to handwriting that the reading mind is still marching on toward meaning when we realize we are no longer standing on logos’ solid ground. We see signs that can no longer direct us; it seems that wherever we have ended up, our own language is no longer spoken here.

Enter inference. Twombly’s writing marks have been referred to as gestural, iconic, aniconic, calligrammatic, evocative of runes, akin to graffiti. The ancient Greek word for the verb to write is graphein, which means to inscribe, incise, scrape off. Naturally the ancestral derivation of our current meaning may speak more to the process by which writing was made than to the conceptual implications of overlay and removal, or subtraction versus addition of material or meaning. Yet it is in the paradoxical midst of these echoing processes that Twombly’s para-mimetic glyphs both approach meaning and slip it, the way the populace of dashes in Emily Dickinson’s poetry simultaneously link and separate lines, are as much a part of the language as words, and suggest a trailing of mind from words into that for which there are no words, while also acting as a lifeline back from that realm.

In reading Twombly’s writing marks one finds what is presented, not what is represented; that is to say, if his paintings evoke a deus ex machina, it is because he creates a past-present allusive dialectic through an anachronous linguistic mechanism, or medium. It may be tempting to believe that Twombly’s pictoral context is subsumed by its textual relevance, but it is precisely the relation between the two that offers the viewer the greatest freedom in appreciating the work.

Yet despite direct references to classical text or modern literature, Twombly’s paintings remain friendly and buoyant in a way that the work of other abstract expressionists did not. Twombly’s paintings, on the other hand, cradle the viewer in safe, natal spaces of beauty often rich with vivid color, yet both entertain and guide us with the element of surprise. The words surprise and suddenly derive from the same root word meaning emerging from beneath the surface. While “Apollo and the Artist” appears to sink chromatically and formally into deeper realms of oracular mysticism, we find we are protected and carried up by Apollo and the artist, since Delphi shares textual allusion to a dolphin by way of delphus, a Greek word associated with womb.

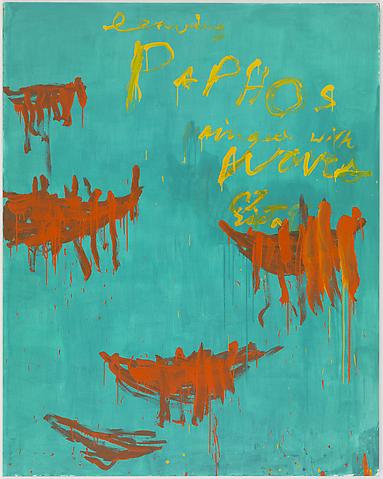

So while Twombly worked heavily with literary allusion, referencing well-known poets such as Alexander Pope, Rilke, Yeats, whose works may not be established in the minds of the masses but whose names are generally recognized, Twombly also references utterly obscure poets like the 7th century BCE poet, Alkman, who haunts Twombly’s “Coronation of Sesostris” (2000) and reappears in the four panels of “Leaving Paphos Ringed With Waves” (2009), the words a line from Alkman’s poetry.

I say that the artist referenced literature, but I do not believe as others do that his paintings are referential. One need not know that Paphos was the island home of Aphrodite. To the contrary, Twombly’s work can equally be seen as so strictly self-referential that it is therefore autonomous, in which case the meaning of the work, if there is one, is found within that loop of self to reference to self-reference to simply self again. While Twombly may have delighted in the possibility, however unlikely, that his viewers would rush to their nearest bookstore to take home a ten-pound copy of the Norton Anthology of World Literature, he did not paint solely toward a well-schooled demographic of English majors. In fact, many might argue his true intended audience are first-graders still capable of expression abstracted from meaning or any other establishment of rule.

At the other end of Twombly’s perceived lyric ideology is what art critic and historian Simon Schama calls, in his introduction to the Whitney monograph Cy Twombly: Fifty Years of Works on Paper, Twombly’s “happy-scrappy quality” (“Cy Twombly,” 2004, pg. 17). I love this, and I find Schama’s playful candor a fabulous foil to Roland Barthes, who also supplies an introductory essay for the monograph titled “Non Multa Sed Multum,” in which Barthes poses the question “How does one go about drawing a line that isn’t stupid?” (pg 38). Granted, Barthes’ essay validly defends Twombly against criticism that the child-like nature of the work belies lack of deliberation and want of technical skill, but the question imposes the very aesthetic governance that Twombly rebels against. Twombly’s hallmark technique of scribbling words, near-words, and marks suggestive of words (descriptions for which critics have no shortage of words), hems notions of reference and representation into the realm of the graphical dialogue, one taking place presently with paint, in a language of paint that remains within the painting without the necessary extension of a linguistic dialogue outside of it.

In the late 1960s Twombly completed a series of untitled paintings now commonly labeled the “blackboard paintings.”

Indeed, the paintings, produced using wax crayon and house paint, so resemble a schoolroom blackboard that we might consider why Twombly did not create the same artwork with chalk on slate. The “writing” seems as if it could easily be wiped away, like memory. It cannot. One feels a temporal tension in the work between permanence and impermanence. (Or is it not a tension at all, but a harmony?) In these paintings impermanence is both implied and indelibly denied, held not in a past tense or future tense, but in the past-perfect or future-perfect tense, where things will have already taken place relative to a moveable present. Memory is experiencing the past in the present. To illustrate, bring to mind your experience of learning grammar. The present perfect tense designates something that began in the past, and which continues into the present, or which effects into the present.

Some of you reading this will understand what I am saying. For others, my grammatical explanation sounds like gibberish (again, compare to the sound of Charlie Brown’s school teacher). The dichotomy I have just created by translating the “blackboard paintings” through an analogue language only some of you speak is precisely the broadcast level on which these not quite black-and-white paintings operate: divisions and oppositions between the recognizable and the unrecognizable, the recalled and the forgotten, the insinuation of time on memory and vice-versa that can, at any given instance, evoke entire mysteries of emotion simultaneously and without resolution.

Thus, returning to my question whether one must be scholastic to understand Twombly, I arrive at an inconclusive, but elementary, notion: some inchoate sense that Twombly has been working at the very core of epistemological inquiry. What do we think we know? Where does knowledge come from? And where does it go? How do we distinguish discovery from creation? Where is everything that isn’t here?

Cy Twombly leaves behind a body of work revealing glimpses of his own examination, unique to him alone yet, inscribed by, to, and with the collective human experience. So long as we remain part of that collective, we will have to be content in seeking what Cy Twombly now knows.

—Andra Maguran