A Pound of Flesh

“Thus ornament is but the guilèd shoreTo a most dangerous sea…” —William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

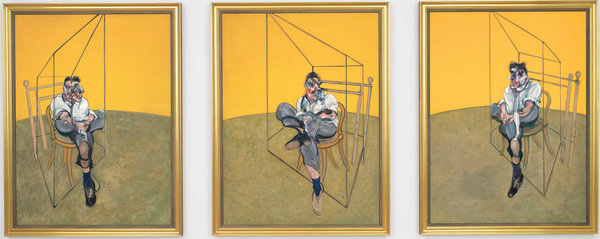

The latests meme fueling the zeitgeist is concerned with the obscene amount of money being spent on art, in this case one very specific triptych by the late Francis Bacon. The painting, Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969) recently sold at auction for $142.4 million, allegedly to Elaine Wynn. Ironically her ex-husband, the casino magnet Steve Wynn famously put his elbow through Francis Bacon’s favorite painter Picasso’s La Reve (1932). Even more ironic, is that after repairing the La Reve, it was sold to the billionaire hedge fund manager Steve Cohen in a private sale for more than Elaine’s Bacon, $155 million dollars. In the gilded age in which we live where people like Wynn and Cohen grow richer gambling with other people’s money and the United States is experiencing the greatest disparity of wealth between the rich and the middle class, it is easy to understand how the shiny object in the room is the point of derision instead of the devices at work behind the scenes.

Unfortunately, this is not only a very old story it is one that ultimately reminds me of little distance we have traveled since the birth of modern art with Cezanne and Duchamp. One hundred and two years after Duchamp painted his Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) popular culture remains confused, and even resentful of abstraction in art. Even Holland Carter, the Pulitzer Prize winning art critic with the New York Times, felt the need in his piling on the meme, to snarkely deride Francis Bacon as he was simultaneously disparaging money in the art world saying the sale of the Bacon painting was “a monument to two overpraised painters for the price of one.” When a writer for the New York Times takes umbrage with one of the greatest painters of the 20th century, we can hardly expect the general public to gain insight into the work. The real conversation here and one that is classically American is that we have always presumed that wealth not only purchases power, but holds greater weight with its opinions. As Americans living in the throws of late Capitalism the dirty secret is that we equate money with ideas. Lets take for instance Oprah Winfrey, the only living African-American billionaire and arguably one of the most powerful women in the world. A woman who has built an entertainment empire on a confessional, dare I say, arena for whiners in a talk show format is capable of dictating what books people will read because people value and trust her opinion. Jonathan Franzen the celebrated American author and intellectual, questioned the veracity of this very notion when Oprah chose his book The Corrections for her book club, ultimately propelling it and him to fame. Franzen said then, “I think she was surprised that I wasn’t moaning with shock and pleasure. I’d been working nine years on the book and FSG had spent a year trying to make a best-seller of it. It was our thing. She was an interloper, coming late, and with an expectation of slavish gratitude and devotion for the favor she was bestowing.” In essence, our culture is beholding to people largely undereducated and primarily motivated by the accumulation of wealth to serve as our taste makers, our cultural gatekeepers. Of course the wealthy have always served throughout time as cultural gatekeepers for the masses, but the biggest difference today is many of the people of great wealth in America today lack any real substantial education or background in the arts, literature or history. Oprah has been bestowed an honorary degree from Harvard and gave the 2008 commencement speech at Stanford. Why? Because those institutions like our central culture, believe that money is all that matters in life and that achieving success equates to making a lot of money. That mythos is even more reinforced when someone like Oprah rises up the ranks of wealth after being a poor black child in Mississippi. This however, does not and should not give her cultural agency anymore than you and I.

The question should not be does Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969) deserve the high price tag it achieved at a Christies’ auction, but rather who are we listening to in order to gain a deeper understanding of the world. Who is serving as the interpreters of the next avant-garde movement? How are we educating our future generations so that they might achieve not just wealth, but a deeper moral and cultural understanding of the world? The challenges we face in the coming decades are like nothing mankind has faced since the end of the ice age. The full weight of climate change will demand an intellectual prowess that cannot be found in the false platitudes of talk show hosts, casino magnets and hedge fund managers. It will require a generation of culturally sophisticated, historically knowledgeable creative thinkers who can see their way through the mistakes of the past and forge a life-saving way forward that preserves human kind. The danger in the money associated with the art market today is not the amount of money or the fact that art is commanding such great fees, proportionally that has always been present since the time of the Greeks and Egyptians. No, the danger is the agency given to the taste makers of today, the people we are entrusting to value what is important to not just our generation but many generations to come. As with the great revolutions of the past, the market will correct itself and the great divide between the haves and have nots will shift back to a more reasonable position. The need is to reimagine our culture as something more than money or we are doomed to serve another culture in the future, perhaps the Chinese.

I don’t care how much the wealthy decide to value one painting over the next in order to attain a false sense of spiritual enlightenment or at its most base, status. Perhaps Elaine Wynn was competing with her ex-husband when she outbid the other two wealthy bidders, nearly paying the same price as Cohen paid for La Reve. I would like to think she loved the Bacon and desired it and wishes to share that love with the rest of us. The fact the painting wound up in the Portland Art Museum avoiding $14 million in sales tax portends a potentially different future. Regardless of what the wealthy think or don’t think when they pay these astronomical sums for works of art because the art market outperforms the stock market is ultimately meaningless. We all need to find meanings in works of literature, art and music as agent provocateurs which push us outside of our normal expectations and closer to a collective understanding of our existence. As Shakespeare eloquently revealed in The Merchant of Venice, our corporeal selves are precious and no price can adequately be placed on it. This is a far more important lesson than the price of art or any other commodity, no matter how inherently potent it may be. Where art does matter is in its ability to remind us of our range as human beings. Francis Bacon’s genius was in his unraveling of the interior selves of others and himself in the form of a painting. That psychology was deeply grounded in the physicality of the body.

“Flesh and meat are life! If I paint red meat as I paint bodies it is just because I find it very beautiful. I don’t think anyone has ever really understood that. Ham, pigs, tongues, sides, of beef seen in the butcher’s window, all that death, I find it very beautiful. And it’s all for sale―how unbelievably surrealistic!”1

Of course when he said “it’s all for sale” he was referring to a meat market, but in today’s art market it could easily be transposed to the paintings themselves. I imagine he would be heartily laughing at the outrageous sum his triptych recently commanded. Bacon was a life long gambler and loved the thrill of chance. The thought of a woman who once co-owned casinos buying one of his works for a huge sum would sure have given him pleasure. Bacon used paint to convey the sensation of actual flesh, because flesh is reality. Buying works of art for astronomical sums may give you social status but it will never give you immortality. Nobody remembers the name of the collector who bought Van Gogh's Irises (1890) which in 1987 commanded the highest auction price at that time at a paltry $53.9 million. Who is remembered and revered is Van Gogh.

I recently went to visit with the now infamous triptych at the Portland Art Museum and as with the last viewing of Bacon’s I had at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I was surprised at his command of paint. Francis Bacon was a painter’s painter and for those of us who have spent their lives indulging in the struggles of rendering paint into something meaningful, he speaks to us. What surprised me even more than the work itself, was the rapt attention given to it by others in the room. It sits in the basement alcove, completely by itself in its own room with a double bench placed in front of it. It’s church and the visitors that day were clearly finding something more meaningful than the fact they were looking at something incredibly valuable. They may have come for the spectacle of visiting with something worth $142 million dollars, but they left transformed by the power of Bacon’s abilities. It will be important for us to continually remind ourselves of the importance of great works of art in the coming decades outside of their commodification or any potentially false value placed upon them by their price tag at auction. Yes the art market is rigged so that it can enhance the wealth of the one percent, but that really doesn’t matter as long as we have the basic toolkit to look at work and derive our own meaning from it without dismissing it out of hand because Oprah Winfrey or Eli Broad failed to purchase it for millions of dollars.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtMqbbBZ24w&w=560&h=315]

1. http://aphelis.net/francis-bacon-last-interview-by-francis-giacobetti-1991-1992/