Painting the Wraith

"Both destiny's kisses and its dope-slaps illustrate an individual person's basic personal powerlessness over the really meaningful events in his life: i.e. almost nothing important that ever happens to you happens because you engineer it. Destiny has no beeper; destiny always leans trenchcoated out of an alley with some sort of Psst that you usually can't even hear because you're in such a rush to or from something important you've tried to engineer."— David Foster Wallace

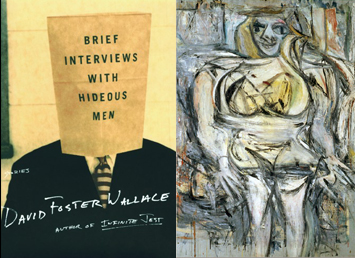

We sit in rapt horror and conflicted emotion when reading Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men whether man or woman. Being a man I can only speak to that gender. The “interviews” conducted throughout the collection of short stories, for a female researcher who’s own character is a composite of those she interviews, form a unsavory landscape of the male ego. As a man you feel conflicted by your want, if you have any shred of dignity or empathy toward women, to feel disgust and repulsion toward many of the comments by the interviewee’s. Unfortunately, you also feel a tinge of identification with them as well. Within you is the understanding we are complex and confused animals often at the mercy of the opposite sex (and hope the opposite sex feels the same, but our fear prevents us from asking). This confusion takes on the form of gamesmanship, whereby we attempt to out-think, out-maneuver and out-wit women in what we believe an elaborate plot to unhinge us, leaving exposed, an empty shell of bravado, hubris and testosterone. Checkmate! Queen takes King.

In the early 50’s Willem de Kooning produced a series of portraits that helped form the foundation of Abstract Expressionism. This series of six “Woman” paintings created between 1951 and 1953 are evocative of the ambiguity Wallace so adeptly portrays fifty years later in his collection of Interviews. de Kooning’s relationship with women and specifically with his wife Elaine, was as complex as any of the interviews in Hideous Men. The power of the “Woman” series is in their ambiguous approach both physically and psychologically in portraying women. On the one hand these paintings are abstractions of women that can be seen to objectify (exaggerated breasts and big eyes) women as sex objects intended solely for the male gaze. This was the model moving through the sixties prior to the women’s liberation movement, and arguably remains a steadfast fixture within our culture today. It is also, under the surface a revealing gesture of the desires we are hardwired biologically to express to procreate. Abstraction after all is a simplification of the truth, the truth of seeing. de Kooning felt these desires and complexities of human interaction as a way of pulling previously unquestioned gender roles into the 20th century. In all likelihood, this was an unconscious act resulting in the paintings. Willem’s love for Elaine ran deep and despite a protracted period of estrangement and contention they never divorced. Elaine tirelessly promoted Willem in the early period of his career and is credited with his meteoric success much in the way Lee Krasner promoted her husband, Jackson Pollock. Elaine was a force to be reckoned with and despite working hard on behalf of Willem, built her own career as a painter and writer. Willem’s “Woman” paintings reflect the intense psychology, specifically of Elaine but of women in general. The powerful expressive quality of his brush strokes and color emulate this intensity, this hidden power within all women. Willem de Kooning’s Woman III is the Venus de Milo of our time, the winged Nike of Samothrace. It is homage and objectification, desire and respect — in essence of a majestic abstraction of the female archetype for the 20th century.

The postmodern age with all of its simulacra and simulation has confused and distorted our most basic of human understandings and emotions. As the writer Chris Hedges says we live in a kind of “moral nihilism.” In his latest book, Empire of Illusion he says we live...

“In an age of images and entertainment, in an age of instant emotional gratification, we neither seek nor want honesty or reality. Reality is complicated. Reality is boring. We are incapable or unwilling to handle its confusion. We ask to be indulged and comforted by clichés, stereotypes, and inspirational messages that tell us we can be whoever we seek to be, that we live in the greatest country on earth, that we are endowed with superior moral and physical qualities, and that our future will always be glorious and prosperous.”

It is precisely this continuously layered irony with which Wallace was enamored. In his masterfully written expose on television E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction, Wallace writes;

“And make no mistake: irony tyrannizes us. The reason why our pervasive cultural irony is at once so powerful and so unsatisfying is that an ironist is impossible to pin down. All U.S. irony is based on an implicit "I don’t really mean what I’m saying." So what does irony as a cultural norm mean to say? That it’s impossible to mean what you say? That maybe it’s too bad it’s impossible, but wake up and smell the coffee already? Most likely, I think, today’s irony ends up saying: "How totally banal of you to ask what I really mean."

Willem de Kooning witnessed the birth of this ironic purveyance in the early fifties with the prosperity that followed WW II. A dutch expatriate he had the background of a European, steeped in history and culture and the hubris of an American living at the beginning of it’s ascendency as a global superpower. Watching the apocalyptic conflagration of WW II left de Kooning and other European artists with utopian visions that hoped for a world of unmasked sybaritic desire and expression. Women, for de Kooning, became an iconic symbol for such utopian desire as emblematically embodied in his wife Elaine. However, much like Wallace decades later, de Kooning soon found that embracing womanhood solely from the perspective of a male dominated society was enough to grasp the complexities and dualities of the genders. As human’s we seek patterns and solutions to the complexities of life but seldom wish to recognize the paradox that produces in leading ever more questions. Artists do their best to lay bare these ambiguities in life so that we might find solace in beauty and just enough respite to contemplate our own blind, perfunctory postmodern drive to make the world simple. Wallace like de Kooning, laid bare the inherent confusion that comes with being a heterosexual man in the modern era with the hope of showing us all a road back to our most basic humanness. It is precisely the confronting of this ambiguity which offers us a way out of our multi-layered ironic existences. Men often confront women as wraiths, transparent visions of a more fully formed person that seems always out of reach. The uniqueness of the opposite sex should be seen as an apparition of emotional confusion whose dimension we don’t understand, but rather a human partner with a different biology sharing with us the human experience. We must not be spellbound by the wraith but metaphorically paint her into existence in order to free ourselves from the prison of absolutism.

“If I knew where I was sailing from I could calculate where I was sailing to.” —No. 6, The Prisoner