A Clockwork Van Gogh

"It's funny how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen." -Alex, from A Clockwork Orange

2009 the final year in the decade, appropriately of naughts (the decade of 00), is nearing it’s end here in the west. I’m sitting here watching A Clockwork Orange by my favorite director Stanley Kubrick, and I am reminded of Van Gogh. It’s the violence of change, you see that comes to mind as the year draws to a conclusion. Uncertainty is ugly, rough and violent.

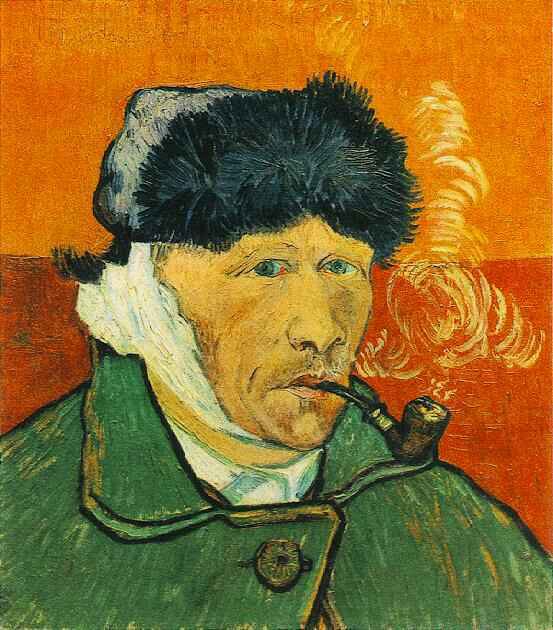

We like to look for order amongst chaos as we humans are responsible for creating more chaos and violent behavior than any other entity on this planet. Van Gogh’s struggle was one of awareness. He saw the world in it’s true form, bright, vibrant to the point of near blindness and aggressive. The potency of awareness can be overwhelming and we find ways of avoiding it at all costs. We hide behind our simulacra and simulations hoping to deaden the persistence of the natural world that we have spent millenia attempting to avoid. Van Gogh confronted nature head on, absorbing it’s vibrant brutality. He wasn’t interested in assimilation but the acceptance of uncertainty that came with the color of the world. Color to him was a metaphor for this natural violence and he emulated it in his own epileptic fits eventually disintegrating into interictal dysphoric disorder. The violence of nature was whole, manifested as a real human existence, not as some simulation or painted reality. Van Gogh attempted to paint what he experienced rather than share some hallucination of the imagined.

In A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick emulates this same kind of violent nature (as imagined by Burgess in the original novel) but within the context of societies’ attempts to cure it as a natural experience. The pseudo-modern world of 70’s future-kitsch serves as the plastic, fantastic background for the escape from the mundane. The lead character imagines the world as purely violent and acts on impulse, as horrible as that can be in its manifestation. Society reacts, aiming to cure the ills of this madness, much as it rejected the imaginings of Van Gogh. Inevitably the cure is worse than the illness and the message is lost on the whole. The real madness of course, is the social constructs that work outside of nature and conceal real experience, thereby leading to violent imaginings as an excuse to avoid the prison of the unreal.

It would be easy to accept beauty as the logical, the imagined math of Bach as opposed to the chaotic emotional violence of Beethoven, but that wouldn’t leave room for the full spectrum of experience. Without the extremes, without the violence of Fauvist imaginings experience grows dull and one outcome is our own manifestations of violence. What is persistent is fear, and it manifests itself in the disempowered. The crooks become cops and the cured protagonist falls victim not only to his own uninhibited actions in the acceptance of the chaos of living, but in society’s systemic reaction to uncertainty. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony becomes the metaphor for pure, emotional confrontation in the movie. What was once an illusive idea, sought after through the lead character’s imaginings, manifested in his violence becomes a prison of the real as he is reformed to fit the mold of society’s banality.

Ultimately, it is boredom and the lack of imagination that bring the ugliness of violence to light. Violence as a metaphor to nature’s potential and persistence of uncertainty is a concept only found in the imaginings of artistic spirit. The healthy manifestation of reality is found in our acceptance of uncertainty and the balance between Bach and Beethoven not the contradictory competition between the two. Salvation doesn’t live at the end of a cure or rehabilitation from real experience, but in the acceptance that we are responsible for our natural position within the world and our acceptance of it’s uncertain consequences rather than our persistence of our own violent acts. A Clockwork Orange brilliantly outlines the holistic responsibilities at play that are the complex interactions of human beings - natural, and real, not fictional inventions of our own.