Free Bird

A review of the movie Birdman (2014) - spoiler alert.

“If I leave here tomorrow Would you still remember me?”

― Free Bird by Lynyrd Skynyrd

In a world encased in irony and cliché the hardest art to produce is that which wades right into that milieu and inverts it, onto itself. The movie Birdman against all odds, does just that. Alejandro González Iñárritu’s wonderful new movie behaves like a stone skipping across the pond of popular culture. With every scrape against the surface, it reveals a deeper, often sadder truth about our culture while simultaneously tearing at the fiber of the system that perpetuates it.

Iñárritu in Birdman has created a macroscopic view of our cultural landscape using the microscopic lens of an 800 seat theater on Broadway in New York and a play by the late poet, playwright and short story writer Raymond Carver. Carver’s play What We Talk About When We Talk About Love serves as the foundation for the move. The production is being staged by Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) an ex-movie superhero named Birdman, whose fame faded with the last of a blockbuster tripartite in the early 90’s. Funding, acting, and directing in Carver’s play is a somewhat last ditch effort by Riggan to regain attention through art rather than pop culture. Riggan’s shame about how he obtained his fame stands directly in contrast to his penetrating desire to be loved as something richer. Against this backdrop Riggan must contend with a cadre of actors replete with a mountain of their own emotional baggage, his daughter’s cold disdain, and his lawyers’ forceable pragmatism. It is a world anyone could empathize with wanting to fly away from and soar above the streets of New York.

What makes Birdman great is its tempo. The soundtrack is simply a drum kit pulsing out Riggan’s life in syncopation. The jazz drummer Antonio Sanchez created a soundtrack that paired with Iñárritu’s direction, creates an unnerving pulse that rises and falls, pounds and runs silent throughout the film, leaving you with an erratic heartbeat for the film. Iñárritu even puts an actual drummer (Nate Smith) playing the soundtrack visible in the film from time to time to reinforce Riggan’s growing delusion. It is a fantastic device not just for its pacing of the movie but because it suggests the beating heart of our own lives and gently nods at the protagonist of Carver’s play, Mel McGinnis who is a heart surgeon.

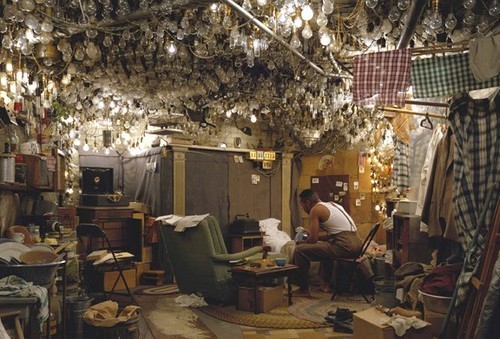

Beyond the use of an aged drum kit for a background, Iñárritu works against fiction and pop culture clichés that thrust the viewer into a bullfight arena of competing pettiness, comedy and tragedy. As a visual artist what I found most striking was Iñárritu’s wonderful use of visual metaphors. A scene in a liquor store mirror Ralph Ellison’s invisible man captured by the photographer Jeff Wall. A fogged filled stage littered with gauzy actors posing with tree filaments on their heads pokes fun at almost every stage production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. A drunk on the street reveals a soliloquy from Macbeth. Even the actors themselves become visual symbols of their own roll in Riggan’s life. Sam (Emma Stone), Riggan’s daughter is bleached out with dark rimmed eye liner making her look like a creepy doll. Mike Shiner (Edward Norton), prances about like a mirror of Riggan’s former self, often barely dressed. In one scene, Shiner is literally the visual metaphor for The Emperor Wears No Clothes. All of these actors and stagings mainly take place in a Broadway theater’s claustrophobic back hallways and rooms, painted in nightclub garishness and faded putrid tones. Riggan’s dressing room resembles more of a prison cell than a lead actor’s sanctuary. Often during the film the chambered back end of the theater becomes the inner chambers of Riggan’s increasingly demented mind where only the stage provides open terrain and safety.

A poignant, keystone scene in the movie leaves Riggan accidentally locked out of the stage door right before the play’s apotheosis. Panicked and left in his tidy-whities (a reference to Breaking Bad?) Riggan awkwardly speed walks around the block, right through Times Square and a crowd of smartphone wielding fans who immediately tweet the experience to over a million followers. On the surface it speaks to the desperation of male middle-age, fading fame, and the cult of personality but what it most beautifully mirrors is Ellison’s Invisible Man;

“I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”

A man whose fame is derived from playing a fictional superhero can stroll through one of the busiest places on earth and yet not really be seen. In this case of Birdman fame replaces race.

There are too many moments in Birdman to recount without spoiling the uncomfortable pleasure of the experience. Few films so eloquently balance comedy with desperation all the while making serious commentary on society, but Birdman succeeds admirably in doing so. The film reminds us of our shared humanity, and our fragility in order to disrupt what seems like an ever increasing reliance on fantasy over reality. Icarus is mentioned in the film but like everything else in Iñárritu’s Birdman, it is not the metaphor it seems. In this case the parable is directed at the viewers not its central character. A society bound to the cult of personality, and superhero movies is indeed flying too close to the proverbial cultural sun and like the Egyptians, Inca’s and Romans before, is destined for destruction. As with Carver’s Mel McGinnis, Riggan’s shame is a grounding force that creates a beautiful destruction in order to reveal a larger truth, “and it ought to make us feel ashamed when we talk like we know what we're talking about when we talk about love.”*

*from Raymond Carver's "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love"