Art & Perfection

Tim’s Vermeer: A Review

“The task is to restore confidence between the refined and intensified forms of experience that are works of art and the everyday events, doings, and sufferings that are universally recognized to constitute experience.” —John Dewey (1)

When I was an undergraduate student in painting we took many cross disciplinary classes, design being one of them. One morning my foundation design professor posed a question to the class for discussion; “If two absolutely identical grandfather clocks were sitting next to each other in a store, one made meticulously by hand, the other only by mechanical means, which one would you buy and would it matter?” This is essentially the question that the movie Tim’s Vermeer is asking. Does the end justify the means in art? Is it art, if the means are purely mechanical?

The root of this question at play in the movie is whether or not Johannes Vermeer, a 17th century Dutch painter renowned for his cinematic portrayal of everyday Dutch life, used mechanical aids in order to produce his paintings. This question sets Tim Jenison on an obsessive quest to try to discover the truth about Vermeer’s methods. Tim is a wealthy entrepreneur who gained notoriety and success by inventing the Amiga Video Toaster®. The Toaster revolutionized video editing for television. Today the majority of television stations use tools made by Tim’s company NewTek, to produce the graphics that inundate our news and sports productions. Tim’s computer graphics background gives him the unique ability to understand optics and color projected through light rather than reflection. From a simple physics standpoint, the type of light that Johannes Vermeer experienced would have been almost entirely, natural or reflected light. Reflected light is the light produced when certain wavelength of light are reflected off of surfaces resulting in the spectrum of visible color. In artistic terms, this is the CMYK light of printing (Cyan, Magenta, Yello and Black or K). However, in today’s world of electronics much of the light our eyes perceive from computer monitors, tablets, smart phones and televisions is projected light or RGB light (Red, Green, Blue). Painters in the 17th century were essentially using paint to mimic what they say using the same physical properties of light. Both human flesh and paint reflect wavelengths of light to produce certain colors. What Tim Jenison claims, is that when you look carefully at Vermeer’s work you see a different translation, one that uses paint to create cinematic or projected light effects, something impossible to render without the use of optics that change the way color, light and shadow behave.

Johannes Vermeer was born to relatively modest means, his father a middle class entrepreneur of sorts, dabbling in silk-working, inn keeping and art dealing. The 17th century Netherlands is referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. The tiny northern European country grew to be the wealthiest nation on earth during the better part of that century. Being middle class Dutch in 1632 when Vermeer was baptized, meant a relative life of comfort. Vermeer’s life paralleled the emergent empire, witnessing the terror of the Thirty Years’ War, and the great conflagration of 1654 known as the Delft Thunderclap that destroyed the greater portion of the city of Delft, Vermeer’s city of residence. These were vibrant and turbulent times for the Netherlands and Vermeer lived at its cultural center.

A compelling mystery surrounding the painter some consider to be the greatest Dutch painter in history, is the lack of information about how he actually became a painter. There is no direct evidence that Johannes apprenticed with another painter, despite being surrounded by many accomplished practitioners in Delft. No record has survived of such an apprenticeship. If you wanted your son to be a painter in 17th century Delft, you had to choose an apprentice he would train with for four to six years beginning at the age of 15. Despite the lack of evidence of his apprenticeship, it must have occurred because he was accepted into the Delft Guild in 1653, six years after his fifteenth birthday. It was impossible to be received into the Guild without the required proof of such an apprenticeship.

Painting and sculpture in the 17th century was firmly seated in the idea of craft. It did not have the open, imaginative associations we place on fine art today. A young boy (women were not allowed to apprentice) would be sent to apprentice with a master and educated in many of the cultural foundations considered important at the time.

“In the master's studio, the apprentice was exposed to the thoughts, opinions and artistic theories which circulated with great rapidity between artist's studios. A number of Dutch painters had traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Masters and returned with knowledge of new techniques and styles which were rapidly diffused. Painters' studios were often lively places frequented patrons and men of culture. Animated theoretical debates and exchange of practical information concerning the art market must have been the norm.” (2)

Being sent to an apprenticeship was no small matter for the families who sent children. At a time when standard education cost two to six guilders per year, an apprenticeship with a Dutch master painter would have cost up to 100 guilders a year. This is a rather important point the film ignores around the question of Vermeer’s skills. (3) To watch the film you would believe that because no record of his apprenticeship exists he was an in situ genius who produced masterworks without foundation and therefore, as the argument goes, must have required special tools with which to create his unique paintings. Genius is an often overused and misappropriated term in our society, tossed about and applied to anyone who appears to have a modicum of talent and enterprise above the norm. There were many, many gifted, classically trained painters at the time of Vermeer’s Delft occupation, Rembrandt chief among them and many more followed. The key component of Vermeer’s work, and one the film does great justice to, is his manipulation of light using pigment. Vermeer’s paintings unlike any other contemporary, are photorealistic. As Tim Jenison quite acutely points out in the film, Vermeer’s paintings are cinematic not painterly. This is the trigger for Jenison that makes him believe Vermeer must have used tools like the camera obscura widely available at the time. Although no such device was found at the time of Vermeer’s death, access to sophisticated optics would not have been hard to come by in the time of the Dutch Golden Age. The Dutch were master traders, and the flourishing of Dutch science at the time made mirrors, telescopes and optics readily available and understood.

I was skeptical ahed of the film, due in part to the fact that Penn and Teller, those shit-stirring, iconoclastic magicians from Las Vegas were behind the project. Having watched their show Bullshit in the past, I knew they could hold a polemicists eye to certain subjects and their glossy, opinionated approach was based more on showmanship and less on fact. However, Tim’s Vermeer was a pleasant surprise and lacked most of the skewed opinions I was expecting. The majority of the film tracks the intense efforts of Tim Jenison to recreate, as closely as he possibly could Vermeer’s The Music Lesson using optics but reconstruct the actual room up to the tiniest detail that appears in The Music Lesson (1662-1665). The magic (no pun intended) of the film is in watching the painstaking and often agonizing pursuit of one man’s attempt to recreate the stage for a the mid-17th century painting and the painting itself, with no formal painting training.

The film left me with a feeling of genuine respect for both Jenison and Vermeer. Although, based on Jenison’s pursuits it seems entirely plausible if not probable that Vermeer used the aid of some basic optics to create his unique style, it does little if anything to diminish the notion Vermeer had a mastery over the form if not the content. As a classically trained painter in the Delft tradition, Vermeer would have been able to leverage optics to recreate cinematic qualities in his work. These lighting effects in Vermeer’s work would have been nearly impossible any other way given the basic biomechanics of our eyes. Jenison is convincing when he reveals certain details in the original Vermeer are in alignment with things he accidentally discover while trying to replicate it using optics. Despite this reveal, I left the film feeling less interested in Vermeer than ever. I have never been a great fan because I’ve always felt Vermeer’s are cold and emotionless works. At a time when Bernini was creating The Ecstasy of Saint Therese Vermeer was toiling away in his little room in Delft making relatively unimaginative paintings.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ze9r58eHnoc&w=560&h=315]

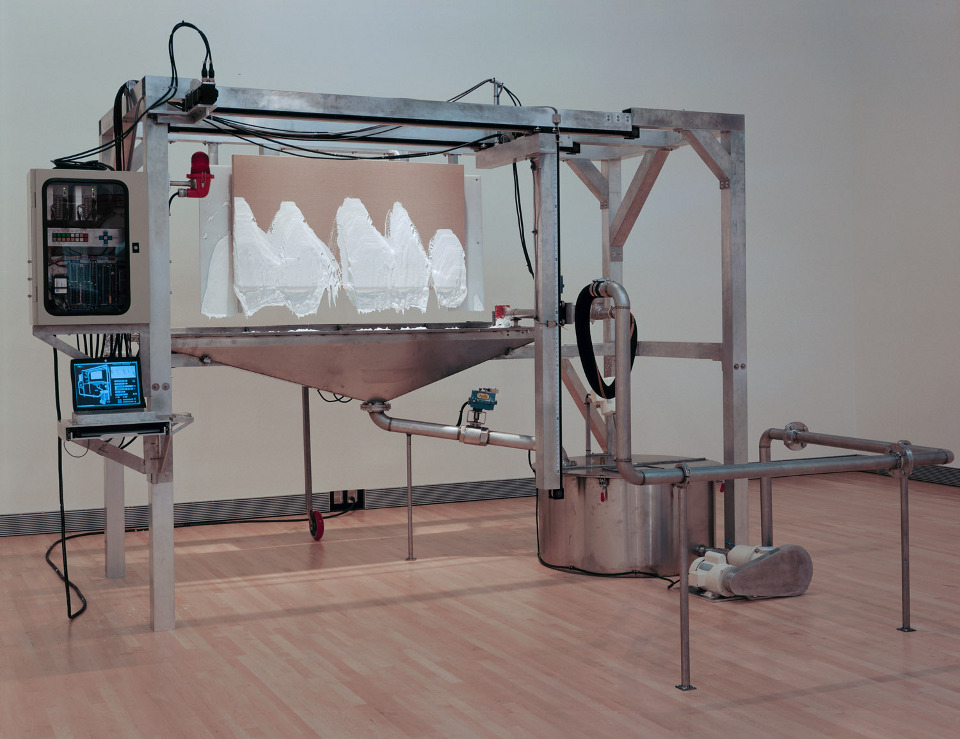

Getting back to the question my design professor posed so many years ago, if mechanical production can match the hand of the artist then what does it really matter? There are now robotic machines that can carve marble into anything you can scan into a computer. Artists like Roxy Paine and others have created robotic painting and sculpture machines, sometimes with compelling and imaginative results. Many blue chip artists today, just like in the time of the Dutch Golden Age, employ assistants and craftspeople to aid or actually fully realize their artistic ideas. Is the power of the Sisteen Chapel diminished when you learn that a group of artisans, many masters at fresco, which Michelangelo was not, worked on the project? In fact many artists reach a certain level of success and find they cannot meet the demands of the market in terms of production and farm out the actual painting of their work to teams. Jeff Koons, and Kehinde Wiley, chief among them. The question isn’t machine versus human. The question is what are the ideas being represented. I don’t care how the hypothetical grandfather clock was produced, only its inherent aesthetic and intellectual value as a creative idea. I would often say to my drawing and painting classes, you can teach a monkey to draw but it will never imagine what we can. Although hyperbole, the point is that the creative spirit is held within the ideas of the artist not with the mechanical production of those ideas, whether by their own hand or by any other means. A paint brush is a tool and so is a camera, hammer, computer, etc., but I defy anyone to replicate a Francis Bacon, Whistler or Caravaggio. Jenison was able to replicate, with reasonable accuracy (I have not seen Jenison’s fake Vermeer or The Music Lesson in person) mainly I think not because Vermeer was a cheat, a conceit to great painting, but because the subject matter and staging were so dull. A Rembrandt on the other hand would be impossible to replicate, not only due to the way it was created (Rembrandt would often use his fingers in the paint) but because Rembrandt’s imagination was far beyond that of Vermeer’s. All one has to do is compare Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring to Rembrandt’s The Slaughtered Ox to see why that is true. Where Vermeer saw middle class convention, Rembrandt saw sex, lust and the meat of of everyday life. Vermeer’s The Music Lesson is a still life of a room filled with static objects and people without character. Despite all the optical, cinematic detail it is still an incredibly boring subject. But, a hanging cruciform carcass of beef tied up in a dark barn with it’s chiaroscuro lighting and rough-hewn paint strokes demonstrate a man who didn’t want to capture a film still of life, but life itself.

Obsession can be one aspect of art making but it is not an essential element. Clearly, even if Tim’s Vermeer is only half true, Johannes Vermeer was an incredibly obsessive person. That however, does not make him a great painter. Our art historical fixation with Vermeer in the modern world is due to our fixation with cinema. We have largely lost our ability to see paintings as more than photographic pastiches. We are no longer educated in the important differences between reflected and projected light because we live our lives staring at tiny screens that project cinematic light. Paintings do not operate in that dimension because they are dealing with the expressly human condition of seeing reflected natural light in our environment, which is how our eyes evolved after our ancestors crawled out of the sea. This leaves us visually and intellectually poorer I think, because we are more and more bound by the simulacra. Vermeer’s uniqueness was in his idea that paintings could be made to look like photography or cinema before either came into being. As Picasso said, “Painting is a blind man's profession. He paints not what he sees, but what he feels, what he tells himself about what he has seen.” I’m afraid Vermeer didn’t feel a whole lot.