46 is 27 or The Math of Artistic Self Destruction

“. . . because art isn't something out there…It is not a "picture" of an artistic experience. It has to become experience itself, and in that sense it can only be earned by one's own body rhythms, one's own color sense, one's own sense of smell, of light, of texture being so automatically articulated there is no possibility not to make a work of art, in the sense that it is impossible to think of any other choice.” —Robert Motherwell

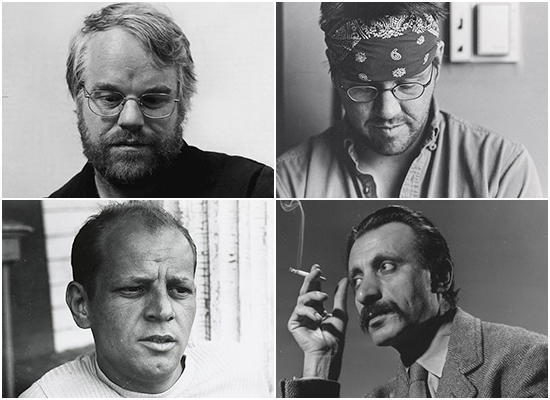

I have always subscribed to Albert Camus’ “…in the end one needs more courage to live than to kill himself.” That is not a trite or easy statement in my mind. It is not suggesting that those that take their own lives are cowards, but they are indeed weak at least at the point of departure. More often than not, intoxicants smooth the way toward oblivion removing doubt and vexing any extant courage. When you reach a certain age—middle age, the weight of being begins to amplify in a way you could not have predicted when young. You accumulate so much that some days you feel as if you’re floating in a river of trash that is making it increasingly more impossible to reach the shore. Artists more than most, are acutely affected by this accumulation because they spend their lives deliberately trying to accumulate, or soak up the world around them, so that they might reflect back that unique experience to the world. Motherwell called it experience, Bacon sensation and Picasso said art was “and instrument of war.” Although I am normally loathe to employ metaphors of violence, Picasso was right, about art. As the saying goes, there are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots. Just insert artist for pilots and you get my point. Of course there have been and are great artists who have somehow managed both the courage and the stamina to fight through to old age, but for some the weight of genius is far too much. This was made poignantly clear once again this past weekend when Phillip Seymour Hoffman took his life with heroin.

I have always subscribed to Albert Camus’ “…in the end one needs more courage to live than to kill himself.” That is not a trite or easy statement in my mind. It is not suggesting that those that take their own lives are cowards, but they are indeed weak at least at the point of departure. More often than not, intoxicants smooth the way toward oblivion removing doubt and vexing any extant courage. When you reach a certain age—middle age, the weight of being begins to amplify in a way you could not have predicted when young. You accumulate so much that some days you feel as if you’re floating in a river of trash that is making it increasingly more impossible to reach the shore. Artists more than most, are acutely affected by this accumulation because they spend their lives deliberately trying to accumulate, or soak up the world around them, so that they might reflect back that unique experience to the world. Motherwell called it experience, Bacon sensation and Picasso said art was “and instrument of war.” Although I am normally loathe to employ metaphors of violence, Picasso was right, about art. As the saying goes, there are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots. Just insert artist for pilots and you get my point. Of course there have been and are great artists who have somehow managed both the courage and the stamina to fight through to old age, but for some the weight of genius is far too much. This was made poignantly clear once again this past weekend when Phillip Seymour Hoffman took his life with heroin.

All artists learn to mimic as way to get through to their own ideas, their own stories, but actors are unique in that their own stories only ever come through in the act of mimicking another’s. For great actors, and that list is very, very small, this must be an even more difficult burden to bear. As with Hoffman, the goal is to so thoroughly inhabit this fictional construct on the page that you make that imagined being whole in a way that leaves no doubt to the veracity of their existence. And yet, within that embodiment you must also lend your own uniqueness, your own personal artistic sensibility but without it becoming apparent or conflicting with the imagined character that was invented on the page. Hoffman himself commented on the difficulty of this strange life he was living when he said,

“Acting is so difficult for me that, unless the work is of a certain stature in my mind, unless I reach the expectations I have of myself, I'm unhappy. Then it's a miserable existence. I'm putting a piece of myself out there. If it doesn't do anything, I feel so ashamed. I'm afraid I'll be the kind of actor who thought he would make a difference and didn't.”

Making a difference to great artists is portraying the baldness of truth. What is hard for us all and seems universal in the mourning for Hoffman is the characters he chose to portray were misfits and oddballs, in other words anyone who is human. He invoked so much humanity in a little gesture or the movements of his face that he made empathy tangible to us, if even for a brief moment. You can do your damnedest to practice Buddha-nature in your day to day when confronted with angry, oblique or even smarmy people, but the truth more often than not, is we do not empathize with these people but dismiss them as outsiders. Hoffman’s genius was to imbue these difficult people with an innate humanity that is impossible to dismiss while watching his acting. As he said, “If you’re a human being walking the earth, you’re weird, you’re strange, you’re psychologically challenged.” Unfortunately, most of all for Hoffman himself, and then his family and then us, is that the weight of this construct inevitably became too much for him to bear. He had experienced too much and slipping back into an old addiction with heroin was all that was needed to ease his trajectory into nothingness.

It occurred to me shortly after getting a text from my brother than Hoffman had overdosed, that another great artist had committed suicide just a couple of year’s ago at the exact same age; David Foster Wallace, another three-named genius. I could easily imagine P.T. Anderson taking on Infinite Jest and ascribing Philip Seymour Hoffman to portray several of the characters from Wallace’s book in a movie, ala Peter Sellers, an acting genius from another time. Both Wallace and Hoffman succumbed to their demons in middled age and arguably at the height of their powers, or at least we’d like to think so. Wallace was very clear in stating his doubts about such powers and I can only imagine, given the previous statements by Hoffman, in combination with his heroin use, Hoffman was facing the same doubt. I suppose you could argue that both Hoffman and Wallace’s work was postmodern in the way they battled irony, emotion and the complexities of humanity, but I think of them more as throwbacks to another time when sincerity was pushed to its limits to manifest itself in the great art movement that was Abstract Expressionism. Where Abstract Expressionism attempted to unravel the banality of evil and the emergence of American hegemony and capitalism, the so-called postmodern work of Hoffman and Wallace had attempted to find a renewed hope and sentimental emotional grounding in this post 9/11 world. Both movements required their artists to dig into the depths of their own psyche’s. Both movements had their victims of that pursuit. This is how artistic accumulation works. A kernel of an idea blooms into a life long pursuit of a very particular (in time) truth and you follow that rabbit down the hole to see where it leads. The hole is dark and deep and some don’t come out on the other side because they forget as Picasso said that “art is a lie to uncover the truth.” The lie becomes the truth and then they fracture. Gorky planted the seed of Abstract Expressionism and then Pollock picked it up and ran with it. For them they were interested in the symbolic aspects of the psyche not the imagined ones of postmodernism today, but their emphasis on sincerity was the same. As Donald Kuspit so accurately pointed out a decade ago in his The End of Art, art has now abandoned any idea of sincerity in exchange for money. Kuspit lays waste to the artist who created a fracture in postmodernism, Andy Warhol to unveil a deeper truth about the loss of authenticity and sincerity in art today.

It occurred to me shortly after getting a text from my brother than Hoffman had overdosed, that another great artist had committed suicide just a couple of year’s ago at the exact same age; David Foster Wallace, another three-named genius. I could easily imagine P.T. Anderson taking on Infinite Jest and ascribing Philip Seymour Hoffman to portray several of the characters from Wallace’s book in a movie, ala Peter Sellers, an acting genius from another time. Both Wallace and Hoffman succumbed to their demons in middled age and arguably at the height of their powers, or at least we’d like to think so. Wallace was very clear in stating his doubts about such powers and I can only imagine, given the previous statements by Hoffman, in combination with his heroin use, Hoffman was facing the same doubt. I suppose you could argue that both Hoffman and Wallace’s work was postmodern in the way they battled irony, emotion and the complexities of humanity, but I think of them more as throwbacks to another time when sincerity was pushed to its limits to manifest itself in the great art movement that was Abstract Expressionism. Where Abstract Expressionism attempted to unravel the banality of evil and the emergence of American hegemony and capitalism, the so-called postmodern work of Hoffman and Wallace had attempted to find a renewed hope and sentimental emotional grounding in this post 9/11 world. Both movements required their artists to dig into the depths of their own psyche’s. Both movements had their victims of that pursuit. This is how artistic accumulation works. A kernel of an idea blooms into a life long pursuit of a very particular (in time) truth and you follow that rabbit down the hole to see where it leads. The hole is dark and deep and some don’t come out on the other side because they forget as Picasso said that “art is a lie to uncover the truth.” The lie becomes the truth and then they fracture. Gorky planted the seed of Abstract Expressionism and then Pollock picked it up and ran with it. For them they were interested in the symbolic aspects of the psyche not the imagined ones of postmodernism today, but their emphasis on sincerity was the same. As Donald Kuspit so accurately pointed out a decade ago in his The End of Art, art has now abandoned any idea of sincerity in exchange for money. Kuspit lays waste to the artist who created a fracture in postmodernism, Andy Warhol to unveil a deeper truth about the loss of authenticity and sincerity in art today.

“Warhol’s art exploits the aura of glamor that surrounds material and social success, ignoring its existential cost. His art lacks existential depth; it is a social symptom with no existential resonance. “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” This consummate statement of postmodern nihilism suggests the reason that art has lost faith in itself: It no longer wishes to plunge into the depth — it doesn’t believe there is any depth in life, and wouldn’t be able to endure the pressure of its depth if it believed life had any — which is why it has become risk-free postart dependent upon superficial experience of life for its credibility.”

There is something in Hoffman and Wallace’s work that wants to unravel this spurious notion propagated by Warhol. Even though as artists they are exploring a new terrain that both led up to and carried us through 9/11 of this imaginary space conflated by ironic gesticulation, there’s is an authentic space disconnected from the conceits of money. Wallace took years to write books and often chose to write low-paying essays instead because he followed his mind. Hoffman was a renowned stage actor who recently played Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman on Broadway. To these artistic geniuses money was nothing more than a confusing object, a demon, not an important component to their work. In fact, this only adds to the sadness brought with their loss because we can see how both them struggled with the inhumanness of money and celebrity.

It would be easy to lament the death of Hoffman, as Wallace, Pollock and Gorky before him, as a loss of a special kind of authenticity, but that would be a mistake. There are authentic artists still going strong who have held on to their courage and not succumbed to the weight of accumulation. The practice of art is in so many ways in parallel to the great mathematicians who have struggled with the concept of infinity (a subject that Wallace himself found dear and consistent with his mathematical background) in that is persistently questions the nature of our reality and in so doing, reforms it. It takes a strong will to step back from this ouroboros of the mind because it would be easy to let go and let it take you. Indeed the nature of what we call postmodernism is concerned with that third level of experience where as Zizek says, “function is dissociated from form.” The normal constraints of the physical world or the symbolic are left behind for a pure exploration of the imaginary. It is not authenticity in and of itself that makes losing genius so hard, it is the combination of empathy and truth. In a world of deadened emotions due to video games, fear, endless war and televisions’ perpetual emphasis on violence, finding empathy in art is getting harder and harder.

There is no lesson to be learned from the loss of Philip Seymour Hoffman, in fact that might be the hardest pill to swallow, but there is encouragement that there are still artists born who retain the wish to go deeply down the rabbit hole on everyone else’s behalf, even if they don’t come out the other side. Hoffman’s death puts a finite point on his career of his own choosing and I prefer to honor that rather than speculate on the greatness that might have been. There is so much to be learned just from his one performance in The Master it reminds me of staring at Pollock’s Lucifer (1947) and remembering what it is to be human.

There is no lesson to be learned from the loss of Philip Seymour Hoffman, in fact that might be the hardest pill to swallow, but there is encouragement that there are still artists born who retain the wish to go deeply down the rabbit hole on everyone else’s behalf, even if they don’t come out the other side. Hoffman’s death puts a finite point on his career of his own choosing and I prefer to honor that rather than speculate on the greatness that might have been. There is so much to be learned just from his one performance in The Master it reminds me of staring at Pollock’s Lucifer (1947) and remembering what it is to be human.